My maternal ancestors

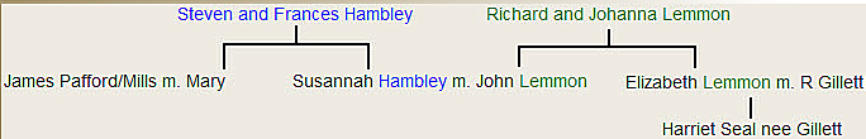

Grtx3 grandparents:

James and Mary (nee Hambley) Pafford/Mills

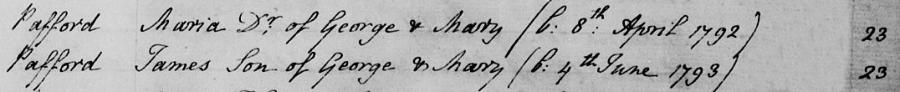

The parish registers provide birth and baptismal dates for

my 3xgreat grandfather, James, the second son of George

and Mary Pafford.

He was born on 6 April 1793 and christened together with

his older sister, Maria, at Holy Trinity, Gosport (shown right)

on 23 June 1793. This church is less than a kilometre from

the harbour’s water edge and a little to the north of the

entrance to Stoke Lake. Glimpses of Portsmouth on the

other side of the harbour could be seen from the church.

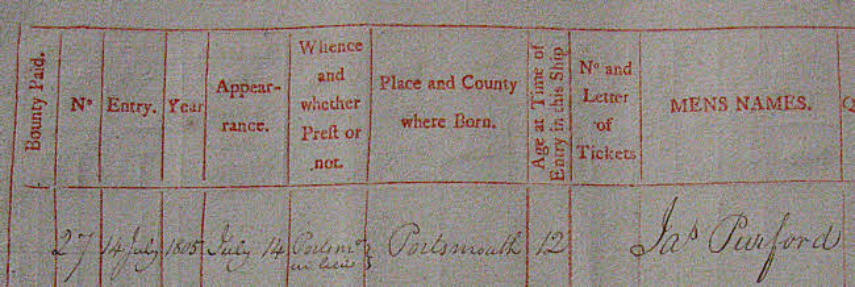

James joined the Royal Navy as a volunteer Boy third rate on

14 July 1805, when he was a month into his twelfth year.

His reasons for enlisting are worth considering. His father,

George Pafford, had served briefly as a mere Ordinary Seaman

on board ships mothballed ‘in ordinary’ at Portsmouth Harbour -

so possibly there was not a strong naval tradition in the Pafford

family. Had George died, so that James had to fend for himself?

A naval historian has noted that most Boys had ‘either been

turned out of their homes or had run away’. Did James’

enlistment hint at an unhappy home life, or did he have a love of

adventure, his head filled with romantic tales of the sea?

Whatever his motives, on that Sunday in the summer of 1805 (a

‘moderate and cloudy’ day) young Jim was rowed out to join

HMS Defence (shown right) which was moored at Spithead, between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight.

Almost immediately, Defence set sail for Cawsand Bay, off Plymouth.

HMS Defence was a 74-gun, third-rate ship of the line, launched on 31 March 1763 at Plymouth

Dockyard. She was one of the most famous ships of the period, fighting at the battles of Cape St

Vincent and the Nile in 1798. Her crew numbered around 700 people.

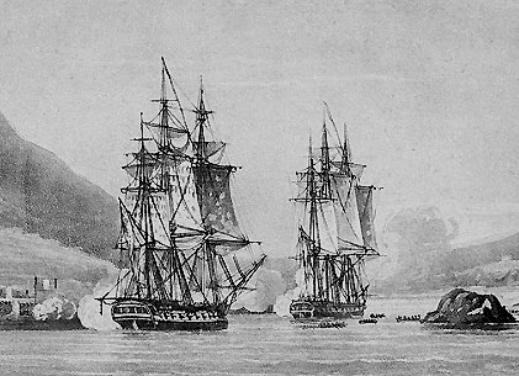

Defence was also one of the most heavily engaged ships during the battle of the Glorious First of

June (1794), and is shown dismasted in the middle of the painting shown below. She is engaging two

French ships. The image portrays the ferocity of the action, with the deck and sides of Defence

littered with broken spars and trailing rigging, the sails of the French ships holed and wreckage in the

sea. The artist is N. Pocock, who was an eye-witness of the sea-fight.

When it was learned that young James was posted to Defence, one can imagine old sea dogs at

Portsmouth Point recounting in graphic detail stories about the ship and James, soaking it all in with

increasing excitement - he was to serve on this famous vessel!

When James signed on, he was noted as ‘Jas Purford’. This is possibly an indication of how he

pronounced his surname. It was recorded as it sounded to the clerk.

James was a ship’s Boy. These lads were generally put to all the dirty

and trivial work of the ship such as cleaning out the pigsties, the hen-

coops and the ‘head’ or toilets. They were often bullied by sailors who

loved ‘to find the opportunity to act the superior over someone’. When

ships weighed anchor, they assisted by ‘holding on and carrying

forward nippers’ which led to them being called, ‘nippers’. Some were

made servants of midshipmen, boatswains or warrant and wardroom

officers. A Boy was allowed half the ship’s allowance of rum (half a

gill) and wine (a quarter of a pint) and pay for the half he didn’t draw.

On this, it was possible to get drunk and be flogged with the

boatswain’s cane. Boys were generally berthed apart from the other

sailors, for good reason, and slung their hammocks in the sheet-

anchor cable tiers or on one of the upper gun decks.

In action, Boys were stationed at a gun with orders to supply it with cartridges

from the magazine. The cartridges were carried using a lidded, wooden

cartridge case into which the cylindrical flannel bag fitted. Being short, boys

were protected behind the ship's gunwale, out of sight of enemy sharp-

shooters. If they tried to run away from the magazine into the shelter of the

orlop deck, the midshipman stationed at the hatchway might shoot them or

beat them back with a pistol butt.

My uncle, Patrick Mills, had told me that his ancestor was a ‘powder monkey’,

maybe dressed like the wounded boy depicted here (right) on board HMS

Victory at Trafalgar with Nelson’.

It is a constant source of wonderment to me that that more than two centuries on, I know where

James was and his circumstances every day of his twelve-year-old life. The National Archives holds

the log books and other records for the ships on which James served which I have copied. It is this

source that reveals that James was at Cawsand Bay, off Plymouth that summer. They also tell us that

he had an early introduction to the rigours of naval life. On 19 July, a sailor died. Then, on 3 August

three seaman were each given twelve lashes as they disobeyed orders and neglected their duty.

In 1805, Napoleon embarked on his Grand Plan to invade England. For this to happen, he needed

the umbrella of a large, combined Franco-Spanish fleet. It took months to assemble the ships, by

which time matters in the Southern Europe had taken a turn for the worse. Napoleon therefore

ordered his Admiral Villeneuve to sail with his fleet for Naples to land army reinforcements.

The log books include the bare bones of what occurred during a ship’s day. The Captain’s remarks

are succinct - typically between three and five lines of writing. He noted that on 7 August 1805,

Defence began sailing down the French and Spanish coast to Cadiz, which is sixty miles north-west

of Gibraltar - arriving there on 27 August. She had joined the blockade of the port which was the

temporary home of the huge French and Spanish fleet which had recently been chased to the West

Indies and back, evading any significant action.

By 4 October, the main English squadron of twenty-seven ships was about fifteen miles from shore. A

handful of ships patrolled Cadiz, watching the activities of the enemy. Defence, Colossus and Mars

were positioned between the two groups, acting as mobile signal-relaying stations,

An officer on Defence wrote, ‘The absence of mood, and the cloudy state of the weather, rendered it

exceedingly dark, so that we came very near the combined enemy fleet without their being able to

discern us. While we concealed every light, they continued to exhibit such profusion of theirs, and to

make night signals in such abundance that we seemed at times in the jaws of a might host ready to

swallow us up. We, however, felt no alarm, being confident that that we could fight our way or fly, as

occasion required. The former was certainly congenial to all our feelings; yet in the face of the

enemy’s whole fleet, we did not regret that out ship was a fast sailor.

At dawn on 19 October, this signal was made from Sirius to Euryalus to Phoebe to Mars to Victory,

‘Enemy coming out of port’. At 09.30 Victory signalled to the Fleet, ‘General chase, south-east’. This

was it! James was about to be plunged into one of the greatest sea-battles ever fought.

The English fleet consisted of thirty-three ships, crewed by 18,000 men. James was one of the

youngest cogs in this huge war machine. Imagine his feelings when he saw the forest of masts of the

forty-one enemy ships that dominated the horizon! The crews cheered and ‘rushed up the hatchways

to get a glimpse of the hostile fleet. The delight manifested exceeded anything I ever witnessed’

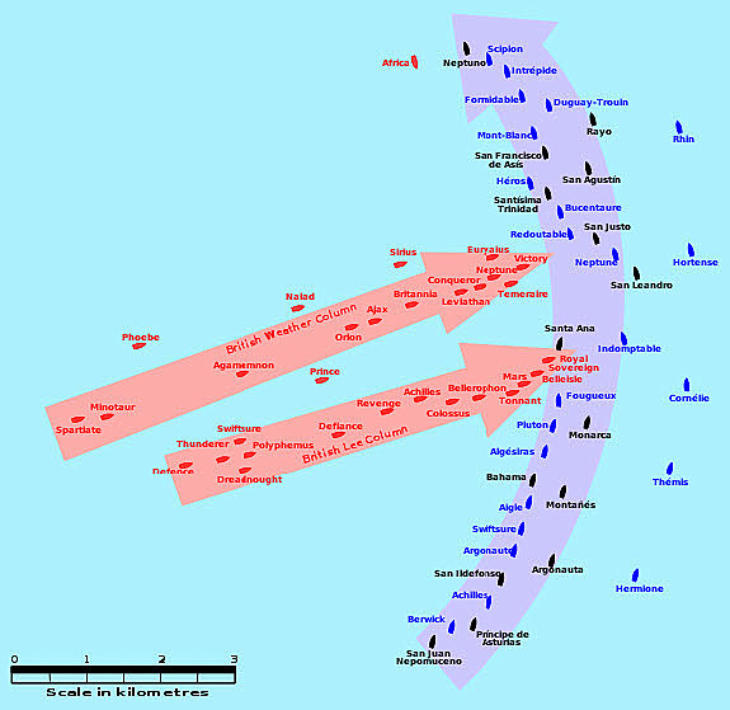

Nelson’s strategy was simple - cut through the enemy’s line of ships, thereby reducing their

effectiveness. Defence was stationed at the end of Collingwood’s line. This meant its crew spent

many hours waiting and thinking of the furore to come, while watching the great battle unfold. At one

stage, the ship was given a ‘hurry-up’ call, ‘Make all sail possible with safety to the masts’.

On 20 October, the Defence’s log book records, ‘Squally with heavy rain….close reefed

topsails…5.50 tacked ship, saw 24 sail of the enemy’s fleet (soon increased to 39)’ Then a signal was

received from Victory: ‘Flags 253, 269, 863, 261, 471, 958, 220, 374, 4, 21,19, 24.’ This well-known

general rallying call does not need to be spelled out.

The signal was ‘received throughout the fleet with a shout of answering acclamation, made sublime

by the spirit which it breathed and the feeling which it expressed’. When it was communicated through

the decks, ‘it was received with enthusiastic cheers and each bosom glowed with ardour at this

appeal to individual valour’. However, this was not the case on board Defence:

The painting above depicts Defence. She has lost her masts and is engaging with San Idenfonso.

Then, the Achilles exploded. An officer on board Defence reported, ‘It was a sight the most awful and

grand that can be conceived. In a moment, the hull burst into a cloud of smoke and fire. A column of

vivid flame shot up to an enormous height in the atmosphere and terminated by exploding into an

immense globe, representing, for a few seconds, a prodigious tree in flames, speckled with many

dark spots, which were pieces of timber and bodies of men occasioned while they were suspended in

the clouds’. Amazingly, despite all the carnage (some ships having hundreds of men slaughtered)

Defence lost seven men killed, while twenty-nine were wounded.

During the din of battle, James would have run to and fro over the bloody and splinter-scattered deck

carrying the cartridge cases from the magazine to his allotted cannon and braving enemy fire and the

snipers in the opposing ship’s rigging. At 5.20, Defence reported ‘several ships dismasted; several

prizes in progression’. But while the battle against the enemy was over, another more powerful foe

began to make its presence felt. The Captain signed off, ‘Strong gales and squally’.

The following day, the log reported, ‘Strong gales and squally with heavy rain’. The surviving ships

were signalled to ‘Anchor’. Many captains responded that they couldn’t comply as they had lost their

anchors or their cables had been severed. Defence was one of the few that was able to ride out the

gale at anchor with her prize, San Idefonso. Close reefed’, Defence had her prize in tow and her

Captain interred the bodies of four named men. The print below shows the scene with Defence still

dismasted and hard to control with the wrecks of other ships in the background.

Repairs to the ship took days to complete. Members of the crew were transferred back to Defence

from the prize together with some of the Spanish crew who were then taken to Cadiz. Gradually the

storm abated and some degree of normality was achieved.

Defence put in to Gibraltar Bay on 3 November and came home to Spithead on 2 December 1805.

She anchored there for four days - a wonderful homecoming for James and his family who now knew

that he had survived possibly the most famous sea battle ever fought. However, the Captain’s log

makes no mention of men being allowed ashore and after four days, they received the signal,

‘Prepare for sea’.

So, on 6 December, Defence set sail again, bound for Chatham.

A final footnote. James’ reward for five months work which included the battle and a hurricane was his

pay. He received a total of £1 15s 6d.

On 24 December 1805, the Defence’s Captain’s Log notes, ‘Sent draft of men on board the (HMS)

Thames’. Included among this party was James. He had a new home for Christmas and he was

destined for colder climes. Again, the log books of the Thames are available to copy at the National

Archives.

The last sentence in Defence’s log book for 20 October was, ‘Standing down on enemy with full sail’.

The fight continued into the next day. Defence fought for a furious two hours that afternoon.

Her log, ‘2.20 engaged a French two-decker’. She was evenly matched with the 74-gun Berwick

which she dismasted, leaving her to be captured by another ship. Then, ‘3.15…handed off the Achilles

(a French ship) at which time we engaged a Spanish ship… (San) Idefonso. At 4.15 she struck her

colours…we took her in tow’.

Thames, pictured above in 1813 on the right, was a new 32-gun fifth rate that had been built at

Chatham. Compared with the bulk of Defence, she may well have been claustrophobic initially for

James. She together with Phoebe and Blanche were dispatched to the Arctic to deal with a French

squadron which was reported to be destroying British and Russian fishing and merchant vessels. On

10 July 1806, they were at Spitzbergen, 600 miles north of the northernmost tip of Norway, but

thankfully, by late September, Thames was patrolling the straits of Dover. After this tour of duty, on

13 February 1807, Thames anchored at Spithead.

When Thames paid off, there were thirteen third-class Boys on board. James now made a decision

about his future life as a sailor. In the ship’s pay book beside his name and one other boy’s name is

an ‘R’. This stands for ‘Ran’. James deserted from the Royal Navy at Portsmouth on 28 February

1807, forsaking the £11 pay that was due. Life at sea was no longer for this fourteen-year-old. Despite

this action, six months later he was back on board a ship, even if she was moored in Portsmouth

Harbour.

Did James desert because he was treated harshly - or simply because he yearned to see his family

and was homesick? As he returned to the service six months later, he clearly wasn’t disenchanted

with the navy. It was the only working life he knew. It was the only training he had received.

There is is a family legend that he was ‘caught drunk in Portsmouth and press-ganged back into

service. Fearing his good reputation would be tarnished if he revealed his name to the officers as

simply James Pafford, he gave his name as Pafford Mills’.

While this makes for a good story, one is doubtful about its complete truthfulness. We do know that he

re-enlisted as James Pafford, as we will see. These are the facts based on naval records - once any

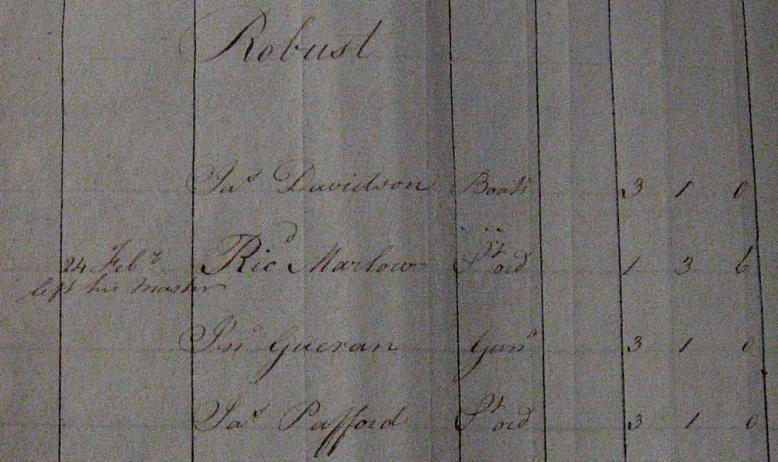

hue and cry for him diminished, James rejoined the Navy on around 28 August 1807 as a Standing

Ordinary Seaman. He was assigned to Robust (3rd Rate, 74-guns) which was moored ‘in ordinary’ at

Portsmouth Harbour. He was part of a twelve-man skeleton crew who were maintaining the fifty-year-

old ship. He was paid £1 8s 6d for the first month and two days work, which is about 5/3d a week

(26p). Then James (now an Able-bodied Seaman) was transferred to Blake (3rd Rate, 74-guns) in the

harbour on 21 July 1814 as part of a ten-man crew. He received £5 10/- for thirteen weeks work -

about 8/- a week - which was on a par with what agricultural workers were earning in the countryside.

Then, James was assigned to Edinburgh (74 guns) on 1 January 1815.

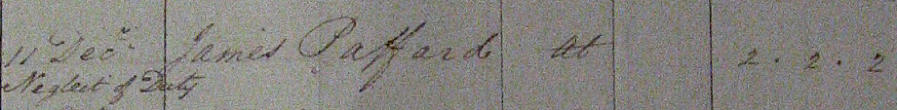

It was while James was on Edinburgh that he and two other able-bodied seamen, John Buttin and

John Akins, were dismissed from the Navy on 11 December 1815 for ‘neglect of duty’. What they did,

or didn’t do to deserve this penalty is not known. However, if their duties are considered, a clue may

emerge. The small crew checked the level of water in the ship’s well; inspected the mooring ropes;

ensured that the magazine was clean and dry; prevented unauthorised entry on board ship as watch

keepers and stayed awake at night, answering the shouts of the Duty Officer as he rowed his rounds.

What was James to do? He was twenty-two and knew only the life of a sailor. As he married a year

later, there may have been additional pressure on him to secure employment. His response to his

predicament was simply to enlist in the navy again, using a different name - arise, James Mills. It

transpired that he chose Mills because it was his mother’s maiden name.

To sign on again under these circumstances was not unusual. John

Crump of Portsmouth Dockyard Museum writes, ‘...I am in no doubt

that a man could have re-enlisted under another assumed name; this

probably happened frequently’. Naval historian, Paul Benyon adds, ‘it

wouldn’t surprise me...as long as the offence wasn’t too serious. The

Navy appears to have been surprisingly forgiving’.

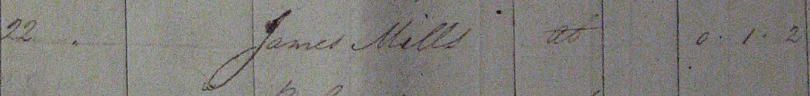

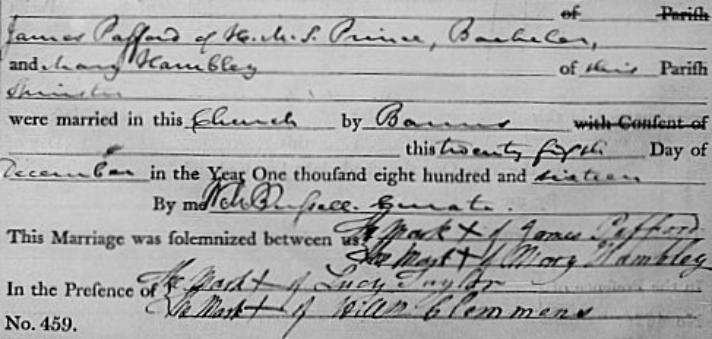

So, James joined Prince (shown right), a ship that had fought at

Trafalgar but was now laid up ‘in ordinary’ at Portsmouth Harbour, on

22 June 1816. He retained his rating as an Able-bodied Seaman.

When he married at St Mary’s, Kingston, Portsmouth later in the year,

on Christmas Day, he earnned £5 8s 10d for thirteen week’s work.

St Marys, Kingston, Portsmouth

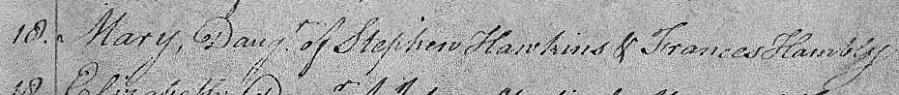

Mary was born in 1793 and baptised on 18 October 1793 at Stoke Dameral, Devon. Her father,

Stephen H Hambley, was a ropemaker at Plymouth Dockyard who moved to Portsmouth in around

1812. Mary’s younger sister, Susannah, married John Lemmon. The two families were inseparable.

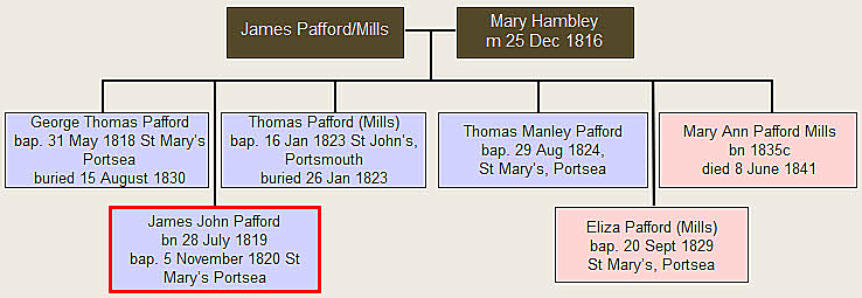

James was still attached to the hulk, Prince, in 1818 when their first child, George Thomas Pafford,

was born and baptised (For naval records, James might now be registered as James Mills, but when

his first children were christened - and buried - he clung to his surname Pafford.)

Where did James and Mary live? According to the parish record of the baptism of George Thomas, at

the end of May 1818, the family were at Dock Row, Portsea, which was near the Dockyard, as the

name implies. By the summer of 1819, according to the pay books of HMS Sapphire, James and

Mary had moved to the enclave known as Portsea Dockyard ‘New Buildings’, (specifically to Sharps

Buildings) where their second child, James was born. (This area and its environment are described at

this link: New Buildings.) In 1820 and 1824, the family were still anchored at New Buildings but when

Thomas, was baptised, they had relocated to Strong’s Buildings, which were situated almost on the

shore line of Portsmouth Harbour.

Just above the baptismal entry for Thomas Manly Pafford in the parish register, the baptism of another

child with the given names,Thomas Manly, is recorded. One might think that this is an erroneous

double entry, but in fact it is the note of the christening of Mary Pafford’s nephew. Thomas Manly

Hambley’s parents, James and Maria Hambley, were also living in New Buildings, at Gravel Lane.

After leaving Prince, by 1822 James was on board the 36-gun Lacedemonian (launched; 1812,

disposed of; 1822) as one of its seven-man crew. His pay had decreased slightly to £5 2s 11d a

quarter. When this ship was taken out of commission, James was transferred to what was to be his

last ship, the 74-gun, 3rd Rate Pembroke. He served on her until 27 March 1836 when she was ‘in

dock’ with a four-man crew. He remained an Able-bodied Seaman. Thereafter, the crews of ships in

Portsmouth Ordinary are listed by the vessels on which they served and not in ‘Portsmouth Ordinary’

ledgers. I have not found James listed after 1836 and, as shown in the census of 1841, he was no

longer a mariner, but a labourer.

As an aside, James’ occupation in 1824 was described as an ‘Extra Master’. This created some

confusion. I was told that this term specifically referred to a highly-qualified mariner who had passed

examinations and had the ear of a ship’s captain when working the ship. This information did not sit

well with what I knew about James, who was probably illiterate - marking not signing when he married

six years earlier. Indeed, in 1822, as his wage of little more than £5 a quarter, when compared to, say,

the gunner’s wage on the same ship (£12 10s), it is clear that his was not an exalted rating. Possibly,

the expression, ‘Extra Master’ in his case, refers to his position on board a ship ‘in ordinary’ in contrast

to a vessel that was under command.

James and Mary Pafford/Mills children

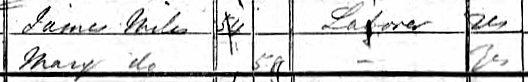

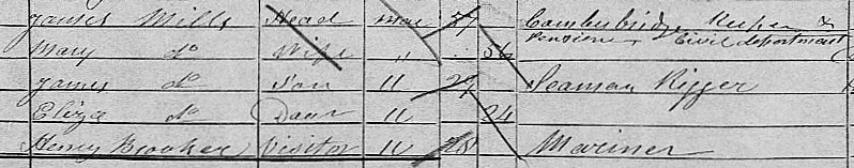

The 1841 census shows the family as living at East Street, Portsmouth Point. But this information

was a little clouded as the family were recorded as Miles and not Mills. However, there were sufficient

signs (for example the proximity of Mary’s sister and husband, John and Susanna Lemmon) that this

was an error. The confirmation that these were indeed my ancestors followed the death of Mary Ann

Pafford Mills two days after the census was taken because her residence was noted on the death

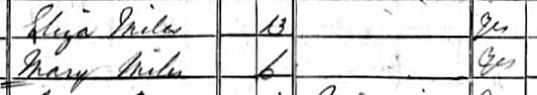

certificate as East Street. She was noted as Mary Miles (6) in the census:

Mary Ann died of inflamation of the bowel. This was probably caused by either ulcerative colitis or

Crohn’s disease. The symptoms include abdominal pain and diarrhoea. The informant of the death

was her aunt, Susanna Lemmon.

As mentioned earlier, by 1841 James was no longer a mariner but a labourer - probably a dock

labourer. Perhaps their move from New Buildings was prompted by Mary’s desire to be near her

sister, Susanna (who was living with her family in Seager Court), and the opportunities for work

around the Camber harbour. Ships’ cargoes were constantly being loaded and off-loaded here.

However, this work could be dangerous. Bulky, heavy goods were swung about and man-handled. In

1864, a dock labourer, John Williams was working on board the Hannah Childs which was moored at

Town Quay. He died after falling into the vessel’s hold. Even boarding boats was hazardous: planks,

only eighteen inches wide, spanned the gap between the quayside and the vessels and it called for

‘perfect equilibrium’ to cross using them. A fisherman, Henry Lingward, died in 1964 simply because

he fell off a plank. Factor in a weighty load, and a crossing became even more unsafe.

In 1851, James and family were still living at East Street. The census details suggest that next door,

or maybe in the same building, were John and Susanna Lemmon. James was now the Camber

Bridge Keeper. With a flourish the enumerator added that he was also a pensioner and that his was a

civic appointment.

The swing bridge connected the sea-end of East Street and the Town Quay. Although more than

eighty feet in length, the bridge spanned a gap of 54 feet and was in two halves which swung up and

down to allow vessels access to and from the Inner Camber. It was surfaced with three-inch planking

and carried a carriageway that was 9’ 6” feet wide and footways, 3’ 4” inches wide.

The bridge was opened on 14 June 1843 as part of the improvements to the Camber. Its purpose was

to provide a short cut between Portsmouth Point and the areas of Portsea, Landport and Point’s

ferries to Gosport and the Isle of Wight. Now, workers in the Dockyard who lived at Point didn’t have

to follow the shore line to get to work. In 1860, it was noted that ‘the bridge was in a great

thoroughfare and had immense traffic over it’. As well as horses and carts, oxen and other livestock

were driven over the bridge.

The duties of the bridge keeper were to open the bridge and monitor the traffic that crossed over it.

But, the bridge was also a focal point for trouble and disturbance. In October 1848, the Hampshire

Telegraph directed ‘the attention of the police to the nuisance committed by the boys and crews of the

potato vessels in the Camber who are in the constant habit of throwing potatoes at the passengers on

the bridge...’. In January 1851, four boys were charged with pelting an agent’s clerk with ‘sprate and

scud’ from the bridge as he passed underneath in a boat.

Then, in September 1854, two men were charged with assaulting John Wood who was engaged at

the Camber Bridge. He was opening it when the defendants, who were labourers on colliers, knocked

off his hat six times, hustled him and jumped down on him. All the while there was a crowd throwing

stones and ‘otherwise annoying’ Wood. The Chamberlain added that these disturbances were

continually being created on the Town Quay.

James was employed by the Corporation and worked the machinery by which the Camber swing

bridge was moved. This was his job until the summer before his death in 1879. Even then he was

able to do a little work for which he received half pay.

In 1861, James and Mary were at 2 Beals Yard, Portsmouth Point, which was just off East Street.

Almost predictably, next door, at No.1, were John and Susanna Lemmon.

Ten years later, in 1871, James (now 78 years old) and Mary were still in the same immediate area at

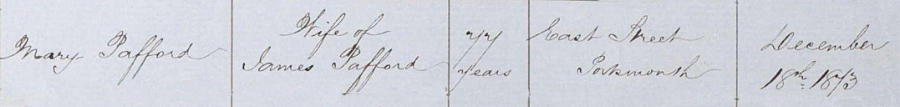

Point alongside the Inner Camber Quay. James was a (naval) pensioner. When Mary died on

11 December 1873, her address was given as 42 East Street, Point. (James and Mary may well have

not moved since 1871 as many of the house along East Street actually backed onto the Inner

Camber, see below).

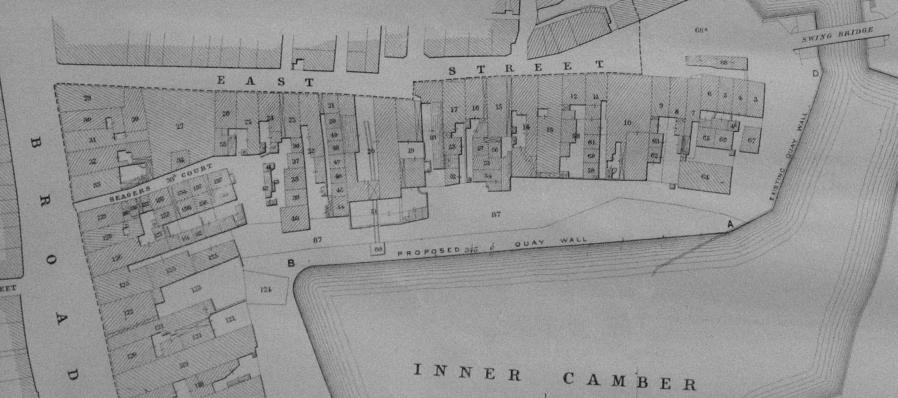

By a happy stroke of serendipity, it is now possible to not only pinpoint where James and Mary were

living, but also to provide a photograph of their home. This is how it came about: I found some

documents detailing improvements to the Inner Camber. These included a map which showed the

dwellings around the south side of East Street. The houses were numbered and a key provided of

who was living in each one. At No. 63 was James Mills and next door (No. 62) was John Lemmon.

Their location may well explain why they were described as being at the Inner Camber Quay in the

census of 1871. The map made it a simple task to now identify these houses from photographs (see

map above). It is likely that James and Mary died in this house.

*

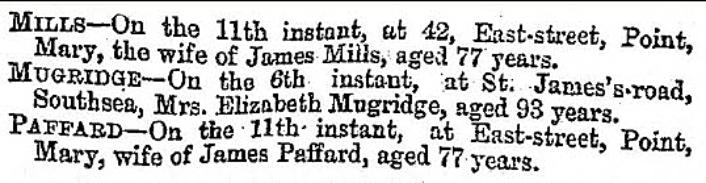

When Mary died, James went out of his way to highlight the change in their surname by submitting

two identical announcements in the Hampshire Telegraph of her passing - one for Mary Mills and

another for Mary Pafford (see below). She was seventy-seven years old and died of ‘senectus’ or

plain old age. She and James were living at 42 East Street and James was described as a ‘wharf

labourer’. The informant of her death was Harriet Mills, Mary’s daughter-in-law, of 21 East Street who

was present at her death.

Mary was buried at St Marys, Portsmouth in Goodyears Plot, 12th Row, 3rd Grave.

Life continued for James at Point. He still worked at the Camber Bridge, although as he grew older, he

was able to do less and less. Probably the annual highlight of his life was 21 October, ‘Trafalgar Day’

when he and a dwindling band of veterans were rowed from shore to HMS Victory which was moored

in Portsmouth Harbour for a celebration of the battle. This tradition had been established by the 1860s

Inevitably at these festivities, the spotlight was focused on men who later became high-ranking

officers despite the fact that most were midshipmen or first-class volunteers in 1805. When they died,

it was as though a victory bell tolled when each funeral was reported. In October 1864, this news item

was syndicated among several newspapers:

“It has been an established custom for the veteran pensioners residing in or near Portsmouth, who

fought under Nelson on ‘Trafalgar Day’ to repair on board the Victory, where they were received with

all due honours. This band has gradually dwindled away. Last year it was represented by three

persons, and on Friday only one was present.”

Likely the ‘one person’ was James Mills who met with a ship’s boat at the end of Broad Street.

Imagine the pride the old man felt when his family and neighbours watched him leaving his home for

the short walk to the shoreline.

Trafalgar Day evolved its own set of unique traditions. During the nineteenth century, Victory was

moored in Portsmouth Harbour. Dawn of 21 October revealed the ship decked out (as shown below)

with its mastheads, mizzen mast, ensign staff and yardarms topped with wreaths of laurel. Sprigs

were placed on the vent holes of each gun and the entrance ports were also decorated. Flags flew

with the epic message, ‘England expects every man to do his duty’.

The total number of sailors, including officers and seamen, who fought with Nelson at Trafalgar has

been estimated as more than 15,000. There were 274 Boys aged between 10 and 14 years -

although the youngest Boy was actually just nine years old.

The last British Trafalgar veteran to pass away, Joseph Sutherland (who, like James, was a powder

monkey at the battle), was born at Sheerness in April 1789 and died on 12 March 1890 at Seaford,

Sussex, aged 101. Browsing the newspaper archives, more than fifty papers reported Sutherland’s

funeral - testament to Britain’s interest in the Battle of Trafalgar and the men who took part.

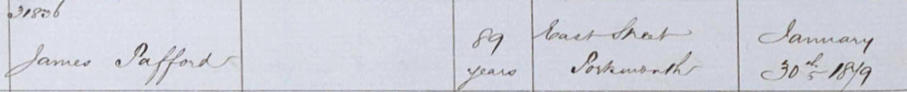

James (naval pensioner - ticket No. 826) died on 24 January 1879 from exhaustion brought on by the

‘chronic enlargement of the prostate gland’. When I mentioned this to a medical consultant, she

remarked, “He must have been in agony”. For James, the act of passing water was a torture.

He was living at 46, East Street and his age was given as 89 years old. Interestingly, the newspaper

death notice described him as James Pafford and the death certificate and burial record was

registered in this name, not Mills. He was buried with his wife at St Marys, Kingston, Portsmouth:

The following is a composite of the news reports of James Mills’ death:

Death of a veteran.

The list of the few remaining survivors of the Battle of Trafalgar was further diminished on

Friday at East Street, Point when the death took place at the advanced age of ninety of

James Mills. The deceased joined the service when fourteen years of age and was on board

‘Defence’ on the day of Nelson’s memorable fight. and on every anniversary of that day a

ship’s boat was sent ashore for him to join in the customary festivities on board the ‘Victory’

in Portsmouth Harbour - returning with him when the festivities were over. Mills was very

proud of wearing the medal which he was awarded and never tired of recording his

experiences of the fight at Trafalgar.

For many years he had been in the employ of the Corporation and used to work the

machinery by which the Camber swing bridge was revolved. He was a hale old man until the

end of last summer when his health began to break and he has not been able to do much

work. The corporation had no power to pension him, so his wages were reduced to half - 8s

a week - and he worked a little when he was able.

This report of the death of a mere seaman was syndicated in at least twenty-two newspapers throughout

Britain - from Portsmouth to Dundee; Bristol to Hull. The reason for this high-saturation coverage must

be because of the ‘local angle’ - James having being born at and living at Portsmouth at his death and

because of the details about him attending the festivities on board Victory on Trafalgar Day.

Yet it wasn’t immediately clear from the records that the James Pafford who had died in January 1879

was my ancestor. Yes, the name and address (46 East Street) seemed ‘right’, but his age was recorded

as eighty-nine when he was actually eighty-five and there were two other James Paffords baptised in

1789-90 in Portsmouth/Gosport (so much for Pafford being an uncommon name!). There was another

stumbling block: the informant of James’ death was a ‘niece’, Harriet Seal, of 15, Havant Street, Portsea.

I had no idea who she was!

After some detective work, I found Harriet Seal - a widow (aged 36, born Portsea) at Havant Street in

1881. I looked in vain at first for her marriage and therefore her maiden name. Then, the denarius

dropped: although she was only thirty-six years old, poor Harriet had lost two husbands. She had first

married Reuben Smith in 1865 and then Henry James Seal in 1871. Harriet’s maiden name was Gillett -

which rang a bell. Gillett’s had been living with Richard Lemmon of 3, St Mary’s Street, Portsea in

previous censuses. I could now put it all together. Richard’s daughter, Elizabeth Lemmon married

Richard Gillett in 1829 at Alverstoke. The couple had five children, including Harriet.

The connection with the Pafford/ Mills family was a little tenuous, however. Elizabeth Lemmon’s brother,

John married Susannah Hambley. Susannah was Mary Pafford/ Mills sister and ‘neice’ can be a catch-all

description for a loose family relationship.

In passing, this research provides fairly convincing proof that John Lemmon had descended from

Richard Lemmon, Now, on the basis of the information provided by a name on one death certificate, I

believe that my greatx4 grandfather was Richard Lemmon and will write his story elsewhere. Link:

Richard Lemmon

Of Trafalgar survivors

Over time, other news stories of ebbing numbers of Trafalgar veterans were printed. The picture

below is of members of the Royal Naval Club at their ‘customary dinner’ at Willis’ Rooms, King Street,

London. It appeared after the seventy-third anniversary of Trafalgar in 1878 - a few months before

James’ death:

The picture was captioned, The Surviving Officers of the Battle of Trafalgar. From left to right, the

seven were: Admiral Spencer Smyth (died April 1879), Commander William Vickery (died may

1882), Admiral WW Percival Johnson (died December 1880), Admiral Sir G Rose Sartorius (died

April 1885), Admiral Francis Harris (died July 1883), Lieut-Colonel James Fynmore (died April 1887)

and Admiral Robert Patton (died September 1883). Clearly these notables were on their last (sea)-

legs when this image was recorded.

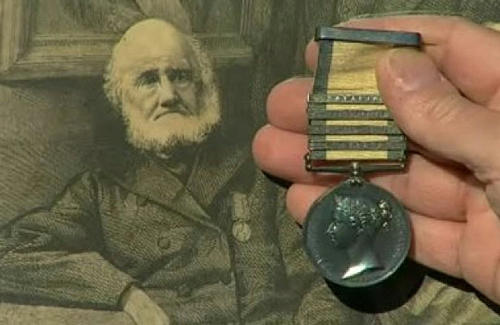

The scene shows three of the notables wearing their ‘Trafalgar medals’. This description is in

inverted commas because no government medal was issued immediately after the battle. It was only

in 1848 that a Naval General Service Medal was minted to which ribbon a clasp was attached with

the name of the battle in which the recipient was involved. Thus, more than one clasp might be

attached - the highest number awarded to an individual was seven! The medal depicted Queen

Victoria and the ribbon was white with royal blue edges. Medal claimants had until 1 May 1851 to

stake a claim. Many, because of illiteracy or limited publicity, did not claim. There is a list of

recipients at Genuki ‘Men of Trafalgar Medal Rolls’ which lists only 1636 Trafalgar clasps being

issued. One was to John Patford or John Radford (sic), a Boy on board Defence - who is clearly

James Pafford.

A story can be told which relates to this and also serves to introduce a picture of the medal and

clasp. In 2010, on BBC’s Antique Roadshow, the greatx3 grandson of Spencer Smyth (shown

wearing the medal, above left) took along his ancestor’s medal and the picture.

In 2018, it was reported that David Mills has ‘the Trafalgar medal earned by James Pafford’.

Reasons to conclude James Pafford and James Mills were the same person

While in my mind there is no doubt that James Pafford and James Mills were one and the same

person, to offer reasons for believing this might be helpful.

James gave his name as ‘Pafford of HMS Prince’ when he married in 1816. The short list of men on

the hulk Prince for that quarter does not include the name Pafford. James Mills is listed, however.

The death certificate of James’ daughter who died in 1841 noted her as Mary Ann Pafford Mills, the

daughter of James Mills.

The double death notice entry (shown above) for Mary Mills and Mary Pafford indicates that they

were one and the same person.

The closeness between the Lemmon and the Mills families – Susannah Lemmon and Mary Mills were

sisters (nee Hambley). As the marriage certificate above shows, Mary Hambley married James

Pafford.

When James Mills died, the news reports after 24 January 1879 noted that he served on Defence at

Trafalgar. There is no record of a sailor with that name on any Trafalgar lists or the records of

Defence at The National Archives. Furthermore, James’ death certificate described him as James

Pafford (not Mills) who died on 24 January 1879.

‘Pafford’ was deliberately kept alive as a middle name in the Mills family. His five grandchildren were

named ‘Pafford’, as were two of his great grandchildren

Oral tradition: the greatx2 grandson of James said that his surname had changed ‘to Gifford’ (sic)

‘because he deserted from the navy

Postscript: a Pafford/Mills descendent visits HMS Victory in 2019

Present-day visitors to Portsmouth Point will find two large and recent additions to the landscape

beside East Street - a boat-park and the new HQ of (Sir) Ben Ainslie Racing (BAR), the Americas

Cup UK Challenge Team which now dominates the skyline (shown on the right, below):

One of team working at the Headquarters as a sail-maker is Ian Pattison - a greatx4 grandson of

James Pafford (born 1783). His sail loft is almost directly above the site of the Camber House public

house, which was where his great grandmother, Mabel Brooks (nee Mills), was born.

Ian’s father, Mike Pattison, remembers Mabel talking about her ancestor being taken out to the

Victory (which was moored in Portsmouth Harbour) every Trafalgar Day as an old veteran, but she

never said he had fought at Trafalgar.

Today, there is a bench at Bath Square which commemorates Mabel Brooks as an “Old Pointer”.

On Sunday, 12 May 2019, Ian was given a personal tour of HMS Victory by her second-in-command.

He found it ‘absolutely brilliant’. His friend had told the officer about Ian and our mutual ancestor,

James Pafford. Ian commented, "I hadn’t realised how significant it was for the crew of Victory to

meet an descendant of someone that had fought at Trafalgar. I was treated like royalty. At the end of

the tour I was taken to the wardroom and after a couple of tots, presented with a beautiful, signed

print of HMS Defence (the ship on which his ancestor had sailed), framed in oak, that was made by

Victory's current head carpenter".

This is a typical example of how the search for ancestors can be hampered - by surnames being

misspelt. There are two lists of men who fought at Trafalgar on the internet. I had looked at these in

the past but they transcribe James’ names as ‘James Purford’ and ‘John Patford’.

It is difficult to imagine how James coped with his terrible ordeal for which nothing could have prepared

him. But unlike survivors of World Wars in the twentieth century, he didn’t keep his experience to

himself. After his death, a newspaper commented, ‘Mills (as he was now known) was very proud of

wearing the medal which he was awarded and never tired of recording his experiences of the fight at

Trafalgar.’

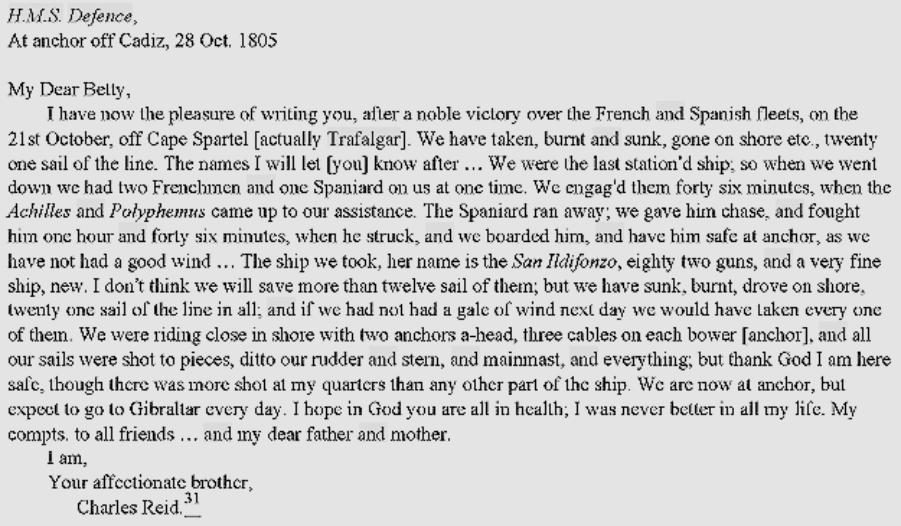

The following is a letter written by a thirteen-year-old midshipman who was on board Defence. It

conveys a young man’s pride in the exploits of the ship of which he was a part - and a sense of relief

because he had survived. Maybe James would have echoed his words:

Ships ‘in ordinary in Portsmouth Harbour

Defence