My maternal ancestors

New Buildings, Portsea

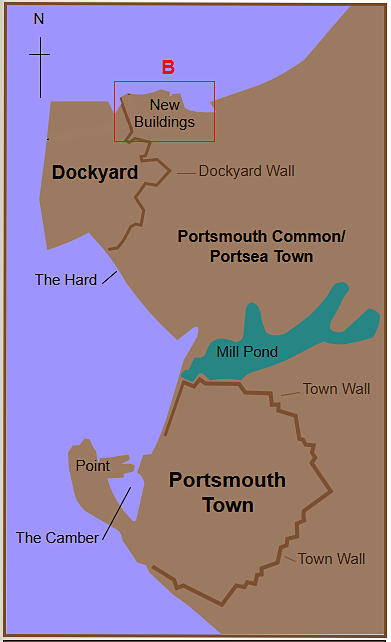

Portsmouth’s western harbour satisfied the criteria for a

dockyard: it is a huge body of water with a deep water

channel; it has a narrow mouth that may be easily

defended and is relatively close to London. So, in the late

twelfth century, a small settlement was established at the

south-west of the island which was named Portsmouth

Town. Among its early thoroughfares (which still exist)

were High Street, St Thomas’ Street, St Nicholas’ Street

and Penny Street. In 1748, Portsmouth Town (protected

by a wall) consisted of 600 houses and 5,000 inhabitants.

Today, it is known as Old Portsmouth.

Extending northwards from Portsmouth Town was a

narrow shingle peninsular which created a small natural

harbour within a harbour. The spit was Portsmouth Point

and the inlet was The Camber. A depiction of Portsmouth

Town dated 1545 shows no houses at Point but some

maritime trading activity – a crane and pulleys; men

rolling barrels to load a boat in the Camber. By 1663,

dwellings at Point along Broad Street had been built and

the Camber was a small commercial port (as distinct

from the naval dockyard).

To the north of Portsmouth Town was a large tidal mill

pond which created a natural barrier. North of the pond

was a large tract of land called The Common (not to be

confused with Southsea Common and also described as

West Docks Fields).

Beyond the Common, the Dockyard was built which was

also protected by a wall. To accommodate dockyard

artisans, houses were built on The Common around St

George’s Square and Havant Street.

Above is section B from a sketch dated

1663. It shows the south-west of Portsea

Island ca. 1700 before Gun Wharf and

parts of the Dockyard had been

reclaimed from the sea.

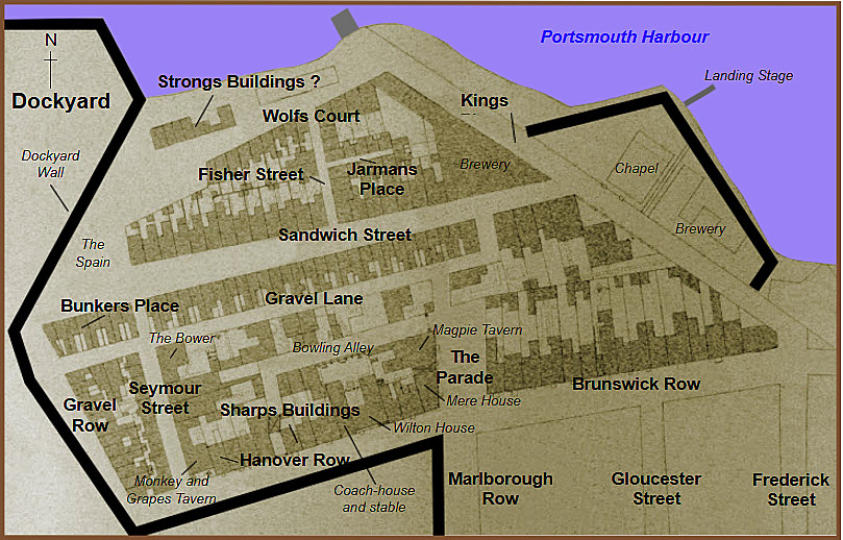

New Buildings (section B from the first map) when they were taken into the Dockyard

in 1847. This area was approximately 200 metres wide by 100 metres.

I am particularly interested in this area as some of my family lived here. The papers of

HMS Sapphire record that my greatx2 grandfather, James Mills, was born at Sharps Buildings in

1819. They had moved to Strongs Buildings by 1824. A branch of my ancestral Hambley family

was living at Gravel Lane also in 1824.

However, by 1841, the Mills’ had moved to East Street at Portsmouth Point.

By 1700, Portsmouth Town, with its constraining walls, was bursting at the seams. The pressing need

for new homes was given impetus and direction by the distance that Dockyard artisans had to travel

to their place of work.

The result was a new housing development at Portsmouth Common, despite the obstacle posed by

the decree that ‘no person can erect buildings or do anything to the prejudice of the Kings

fortifications’. Thus, by the beginning of the eighteenth century at New Buildings (beside the

Dockyard’s wall to the north-east) there was the first organized attempt to build on Portsmouth

Common – there, sixteen payments were recorded for the Poor Rate in 1700.

An obvious reason for this spot being selected initially was that there was a gate nearby that allowed

workers access to the Dockyard .

The proximity of New Buildings to the Dockyard resulted in an alarm being flagged-up by the Board of

Ordinance in 1699: ‘The new buildings lately erected on the north-east side of the docks are

advanced within fifty feet of the design for fortifying the dock....’

One solution was proposed by T Seymour: The ‘shutting up of the north-east gate at Portsmouth,

whereby they are prejudiced in certain new buildings erected for the accommodation of the dock

workmen...They represent that if the gate be kept shut, their tenants in the new buildings must desert

their habitations’. (NB This gate was relocated in 1709)

The governor of the Board of Ordinance threatened to turn his guns on the newly-built houses of

Portsea but in 1702 the visiting Prince George of Denmark intervened on the locals’ behalf. As a

result, Queen Anne (who was married to the Prince) allowed the building to continue and with this

royal approval, Portsea Town grew rapidly.

Sights, sounds and smells of New Buildings, Portsea

To understand life in the little township, one must sense not only its close proximity to a rapidly-

expanding Dockyard but also that the sea lapped its shoreline at high tide – a landing stage and

landing steps providing access to the township. When local property was advertised for sale, it was

noted as being ‘situate near to the Dockyard’, ‘close to the waterside’, ‘abuts high water mark’ or

‘contagious to water’.

The Dockyard provided background music for the community. New Buildings was dominated by ‘the

busy sound of the Yard. To strangers and visitors it was just a confused and deafening noise. When

you got to know it, you distinguished half a dozen distinct sounds which made up that inharmonious

and yet not unpleasing whole....you could not see it, but you felt it, and knew it was there’.

Another sense, smell, would have been assailed at low tide as New Buildings looked out over harbour

mud. Nostrils were filled with the stench of sludge, decaying seaweed and that double-act, flotsam

and jetsam, which accumulated along the shore line. This offensive effluvia was mixed with the

nauseating odour of odure disgorged from the township.

The streets of New Buildings

The street names of New Buildings changed as national heroes and local personalities emerged.

Thus, Sandwich Street (which was known as Middle Street in 1777) referred to the First Sea Lord, the

fourth Earl of Sandwich, who attempted to root out corruption in the Dockyard. However, his

investigation also uncovered abuses by the workers who lived in these streets! The name, Seymour

Street, first appears in 1796 and was a reference to Lord Hugh Seymour an Admiralty Commissioner

(1795-98). Wolfe’s Court was an echo of General James Wolfe who stayed at Portsmouth in 1758

whilst en route to Canada. Ironically, the General was critical of the Portsea populous which he

castigated as ‘diabolical’. He added in a letter to his mother, ‘It is a doubt to me if there is another

collection of demons upon the whole earth. Vice, however, wears so ugly a garb that it disgusts rather

than tempts’. Despite this, or maybe because of it, the locals still named a street in his honour.

Jarman’s Place, Sharpe’s Buildings and Fisher Street were coined after owners and residents. Gravel

Lane and Gravel Row were so called because they were close to the gravel pits of Portsmouth

Common. Brunswick Street was allocated funds for paving in 1770 - the implication being that the

streets were of mud before this time. The Parade was a place of assembly. Once a year, the

inhabitants elected a mock ‘mayor’ who then sat in state at the Parade as a local company (the

‘Royal Stiffs’) marched past. The ceremony and festivities concluded with great bonfire at what

became known as ‘Bonfire Corner’.

Because of its position, New Building people were mainly mariners and dockyard workers with their

families.

The township’s proximity to the sea brought in its wake specialized trades. Watermen plied their

services at the water’s edge and ferried customers in their wherries around harbour, to moored ships

and also across to Gosport. Wooden ships, temporarily anchored in Porchester Lake or nearby

Fountain Lake, were broken up and their timbers sold by firms such as Clarke and Carter. Cargoes of

coal, house slates and ‘weevil grains’ were landed and sold from stores and yards.

Scattered among residents were the support tradesmen who supplied the community’s basic needs.

New Buildings had two breweries (Prince of Wales and Pink and Collins), at least two taverns (The

Magpie and The Monkey and Grapes), a ship breakers yard, a bake-house, coal stores, a grocery

store (at 19 Sandwich Street) and a coach-house and stables.

Social amenities included a bowling alley, a chapel and a brave attempt of an infant’s school at

Seymour Street which opened in April 1827 and, being funded by public contributions and needing

£100 to survive each year, ran into immediate financial difficulties.

Local trades and amenities

According to the 1775 Rate Book, the numbering of houses at New Buildings ended at 112, which

may indicate the size of the neighbourhood. The homes were well over a century old and, like the rest

of Portsea, in an insanitary state.

The plans of New Buildings show that most homes were terraced with a small yard. In the early 1820s

when properties were sold, sometimes descriptions and rents were included:

·

1805. 19 and 20 Gravel Lane. Annual rent – six guineas each.

·

1829. Three tenements at Seymour Street with cellar, parlour, kitchen, three bedrooms and a

yard. Frontage: 30 feet; depth 28 feet. Total annual rent - £90

·

1832. Seven homes at Wolfe’s Court. Total annual rent - £30.

·

1838. 40 and 41 Sandwich Street. Each with two cellars, front and back sitting rooms, four

bedrooms and an attic.

One sale prospectus helpfully added some details about the water supply to some houses. It detailed

five newly-built homes at 35-39 Sandwich Street (total annual rent - £80) which were ‘plentifully

supplied with excellent spring water and pump’. Indeed the 1846 map of New Buildings shows a well-

house in the vicinity.

The buildings of New Buildings

New Buildings and the 1841 Census

A snapshot of New Buildings emerged on 6 June 1841, when the census was taken. Before

summarizing these figures, it should be noted that these relate to the streets which were taken into the

Dockyard from 1845 as shown in the map above. Not included are the streets that run toward the area

such as Frederick Street, Gloucester Street and Marlborough Row. (It is uncertain whether these

streets were included in the district known as New Buildings.)

The area comprised of 148 dwellings and a further fifteen which were uninhabited - a pointer to the

dilapidated condition of some of the housing stock. There were 725 inhabitants on census night; on

average there were five people to a house but this figure is distorted by the small households of one or

two people recorded at Gravel Lane and Sandwich Street.

The adult population of the area was dominated by royal navy and merchant navy mariners (39), their

wives who remained at home when their men went to sea (36) and naval pensioners (20). Thus, 41% of

adults were connected to the royal and merchant navies.

Many Dockyard artisans were still living at New Buildings. They included shipwrights (9), rope-makers

(4), sawyers (3), joiners (2), blacksmiths (5), stonemasons (2), a painter , a sail-maker , a messenger to

the Port Admiral and a female oakum picker. So, 16% of working adults were employed in the

Dockyard. In addition to these there were nineteen labourers who may or may not have been in the

Yard.

The remainder of workers were the infrastructure of the community: watermen (12),

cordwainers/shoemakers (9), tailors (4), bakers (3), fishermen (2), coal merchant (2), grocers (2),

uncategorized merchants/shopkeepers (5), a miller, a fruiterer, a fishmonger, a draper, a lighter-keeper,

a nurse, a male hair-dresser, a basket-maker, a bricklayer, a cook/pastry cook and a policeman.

Included in this list were those supplying beer and liquor. There were two brewers. Also, three publicans

(two of whom also worked: one as a painter, the other as a tailor) and three licensed victuallers. One

publican was at Wolf’s Court, but the rest were clustered along Sandwich Street.

In the 1830s, the days of New Buildings were numbered. The Dockyard leviathan was again on the

crawl. A sea-change in the construction of vessels from wood to steel and from sail to steam

demanded that the sprawling yard should sprawl some more. On 26 December 1836, a possible

expansion project was reported in the Hampshire Telegraph: ‘...a plan has been shewn us of taking

such increase out of the part of Portsea called New Buildings – a portion of the town very valueless

(italics mine)...’

Sure enough, the death knell of New Buildings sounded in 1844 with the serving of notice of the

Admiralty’s intention to purchase land for its enlargement. The Hampshire Telegraph of 12 July 1845

trumpeted: ‘New Steam Basin’. It reported that ‘the business of removing about 130 occupants from

their various localities has been most ably managed...with one or two exceptions the properties were

of small value’. Yet a few words later, it was stated that ‘many objections at first arose and threats

were held out...’. It concluded that the Admiralty has shown much consideration in ejecting the tenants

and in the cases of three old widows who were merely tenants but who had lived in their respective

holdings for perhaps all their lives, they have been given £8 or £10 a year for the future’.

It might be thought that this report is a perhaps rose-tinted view of the eviction/evacuation. It may

refer to one stage (of several) of the removals; or the ‘130 occupants’ may relate to the adults and not

the children who were wrenched from their homes.

By 1848, New Buildings had become Demolished Buildings.

Top

The last days of New Buildings