My maternal ancestors

Upper Clatford, Hampshire

The name of the village, Upper Clatford, charmingly means, ‘Ford where the burdock grows’. This

immediately provides information about the area - there must a river (for there to be a ford) and the

local ecology supports the prolific growth of burdock (a weed that grows in hedgerows and besides

streams).

Upper Clatford

The village is centered on the River Anton (right) which

is one of the four headwaters that form the River Test

which empties into Southampton Water. Upper Clatford

is two miles south of Andover.

Its backdrop is classic Hampshire landscape - green

and rolling. No stark crags. No dense forests. The

climate is dry but the shallow, meandering Anton is

constantly fed by the water table of the Salisbury Plain,

which is to the north. The area is a happy juxtaposition

of flowing water, meadows, plough-land and easy

communications - just the kind of spot where a small

community would settle.

All Saints Parish Church at Upper Clatford (right) dates

from the twelth century and has had several additions over

the years. One consequence of these changes is that a

large section of the congregation cannot see the altar.

Several of my family, the Dees, Smarts and Dowlings were

baptized, married and buried in this church.

Many of the buildings in the village from 1836 are still

standing today - an echo of bygone years. They include

the Crook and Shears public house (right, and shown on

Tithe Map below) the name of which gives a clue to some

of the local farming activity.

The Upper Clatford manorial Court Baron met irregularly at

The Crook and Shears.

Like so many of rural communities in the nineteenth

century, Upper Clatford had its gentry, its farmers and its

agricultural labourers. In 1851, there were ninety-one ‘Ag

Labs’ included in a total work force of 256 men and

women.

There was also the necessary sub-culture of trades which

supported the farming fraternity - the carpenters,

wheelwrights, bakers and farriers.

Another waterway emerged at Upper Clatford at the end of

the eighteenth century. A canal was cut to Southampton

which shadowed the course of the River Anton.

In the mid-1800s the canal was filled in. It was a ‘late’

canal and proved uneconomical. A railway was built along

it’s course soon afterwards but this was also a temporary

feature as it felt the effects of Dr Beeching’s remorseless

axe in 1964.

In the mid-nineteenth century, many families moved from

Upper Clatford into the cities - Andover, Winchester,

Southampton and London. They were probably forced into

this migration by the poor wages in Hampshire’s rural

areas which sparked the Swing Riots when labourers

destroyed agricultural machines.

Above: some of the cottages along

the main street which were

standing in the nineteenth century

(shown as A on map below)

My last relative to live in the village was George Smart, a son of my great x3 grandfather who died,

unemployed, in the summer of 1874 in Clatford Street.

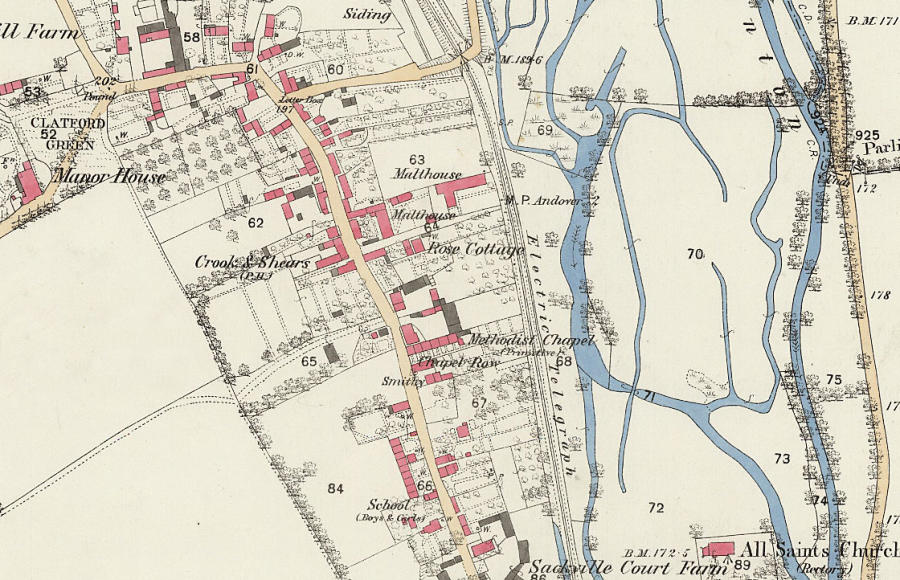

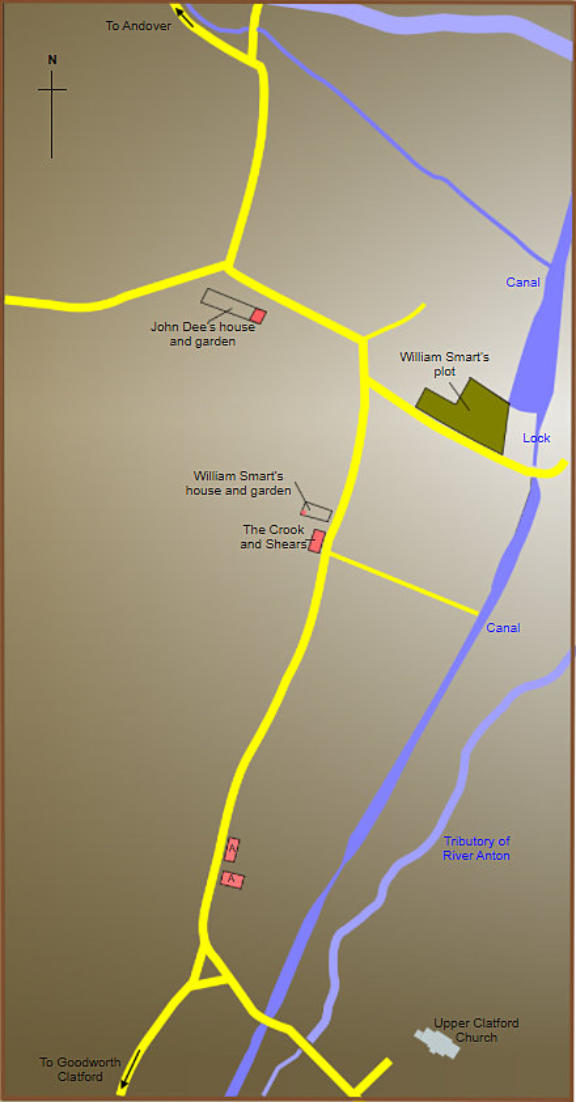

Selected portions of the Tithe map of Upper Clatford (1841) showing the location of

John Dee’s and William Smart’s holdings. (The River Anton flows to the east of the village)

The Upper Clatford ‘Swing Riot’ 1830

The ‘Swing Riots’ of 1830-31 were the violent reaction of farm workers to threatened cuts to their

paltry pay and the effects of enclosure. The written demands of the insurgents were signed, ‘Captain

Swing’.

The rebellion sprung up in Kent and surged through southern and eastern England. Hampshire and

Wiltshire were the counties most affected – each seeing 208 incidents. The rioters burnt ricks and

barns, maimed cattle and destroyed machinery, which was perceived to cause un-employment.

Upper Clatford experienced its own Swing Riot. On 20th November 1830, a mob of 300 armed with

sticks and bludgeons assembled at Andover and, flying a flag, marched to Upper Clatford in the late

afternoon. Their target was Taskers foundry at Clatford Marsh. The foundry was founded in 1813 at a

location that was near the river (which provided power by a water wheel) and a canal (which was used

to bring in raw materials). Taskers made cast-iron ploughs and other agricultural implements and

employed a large local workforce for whom they built houses.

The owners, Robert and William Tasker, became aware that their factory might be attacked and sent

some of their workers to Andover to gather information. These remonstrated with the plotters but failed

to divert them. The mob broke through the locked gates and, seizing material from the factory, began

an orgy of destruction, damaging the water wheel and crane as well as destroying several

manufacturing machines. They broke down the works walls, knocked off the roof and smashed

windows.

When the case came before the court, three ring leaders (including a man who had come from the

other side of London) were sentenced to death. Twenty others were transported.

Looking up the street from the Crook and Shears

1908

1899

1855