My maternal ancestors

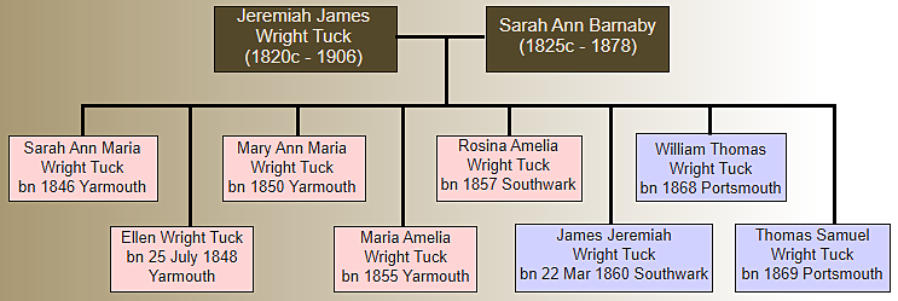

My grtx 2 grandfather: Jeremiah James Wright Tuck

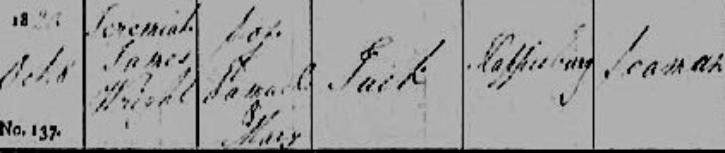

Jeremiah James Wright Tuck was born around 1820 and baptised on 8 October 1820 - the son of

Samuel Tuck, a sailor, and Mary (nee Wright). His childhood home was Happisburgh (pronounced

Hazeber by the natives) which is located on the coast of Norfolk, seventeen miles north of Great

Yarmouth. Now and again Happisburgh features in news stories as yet another section of its land

succombs to the pounding of the North Sea.

Jeremiah Tuck’s family

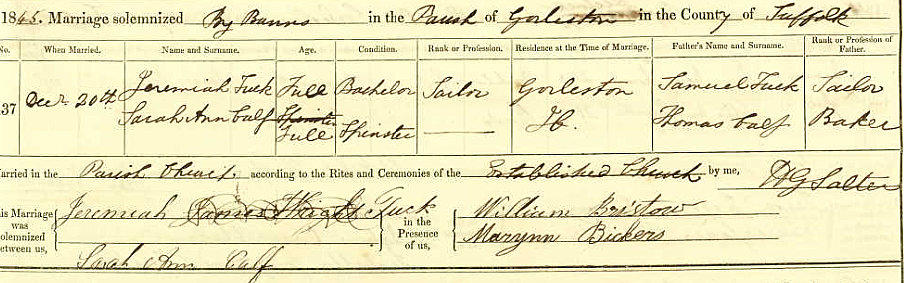

As a young man, Jeremiah followed in his father’s wake and became a sailor. Then, on 20 December

1845 he married Sarah Ann Barnaby at Gorleston (which is just to the south of Yarmouth). Both

husband and wife were literate as they signed the marriage register.

In late 1846, Jeremiah and Sarah Ann had their first child - Sarah Ann Maria Wright Tuck. When their

second daughter, Ellen Wright, was born, the family was living at North End, Yarmouth and Jeremiah

had left the sea and was making ends meet as a shoemaker.

The Tucks in London

Trying to trace the household in the middle of the eighteenth century is a little difficult. They moved to

London and were living at Whitecross Street, St Giles, Cripplegate in 1851. Jeremiah was a factory

engine (or machine) driver. About this time, it appears that he became passionately interested in

friendly societies. Nine years later, they had moved south of the Thames to Kings Court, Suffolk

Street, Southwark and Jeremiah described himself as an engine (machine) fitter. By 1861 they had

relocated again to 3 Williams Place, Lambeth and Jeremiah was still involved in industry as an

engineer.

It would be obvious to conclude that the family lived in London throughout this decade (and two

children, Rosina Amelia Wright and James Jeremiah Wright Tuck, were undoubtedly born there) yet,

in 1851 and 1855, two other children - Mary Ann Maria Wright and Maria Amelia - were born back in

Yarmouth. Probably, Sarah Ann simply returned to her home for the birth of these daughters – a

probability which becomes more of a certainty when we take into consideration that her mother was a

nurse.

And so to Portsmouth

In around the mid-1860s, the family moved from London to Portsmouth where the two youngest

children were born - William Thomas Wright Tuck (1869) and Thomas Samuel Wright Tuck (1870). In

1871, the family was settled at 3 Chapel Row (which was later called Admiralty Row - see map dated

1871 below) which was near the sea at Portsmouth Harbour and skirted the walls of the naval

Dockyard. Two of the Tuck daughters were to marry Dockyard shipwrights.

That Jeremiah had an attachment to his mother’s family may be inferred from the christening of all of

his eight children with his maternal family name, Wright. While on the subject of names, he was also

inclined to inform census enumerators and others that his first name was James.

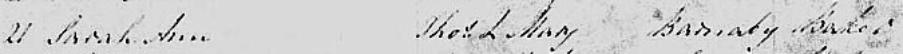

Sarah Ann was christened on 21 November 1825 at St Nicholas, Yarmouth. She was one of nine

children born to Thomas Barnaby (a baker) and Mary Ann (nee Calf). When Sarah Ann married, she

gave her maiden name as Calf. This may well show some antipathy towards her father who was also

blanked by Sarah Ann’s sister when she married. The likely reason for this is that Thomas became a

bankrupt in 1839 and his family endured hard times as a result, culminating in his early death and his

widow’s eventual descent into Yarmouth Workhouse.

Portsmouth

Dockyard

In 1871, Jeremiah was not at home on census night. He was lodging at Christchurch, Dorset where he

was on Friendly Society business (possibly recruiting new members) working as a life assurance agent

- a calling/occupation which was to last for a further thirty years.

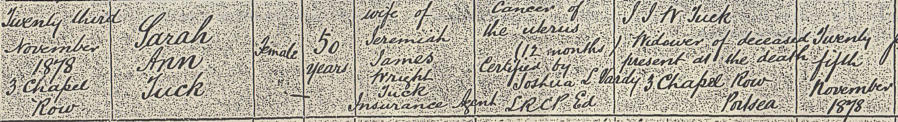

On 23 November 1878 Sarah Ann died at Chapel Row from cancer of the uterus which had been

diagnosed twelve months earlier. She was buried at Highland Cemetery, Southsea - A Plot, 6th Row,

12th Grave.

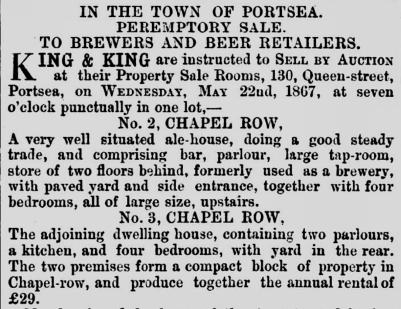

The following advertisement appeared in the Portsmouth Times on 18 May 1867, which may have

been the piece seen by Jeremiah which resulted in his renting the property:

Jeremiah - widower

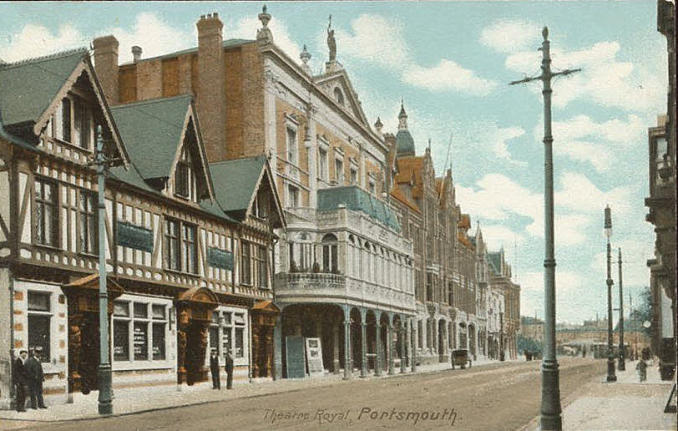

Three years after her death, Jeremiah had moved a little inland to the main thoroughfare of

Portsmouth at 31 Commercial Road where he was the beer retailer of the The Gem (which was a few

doors away from the Theatre Royal). Jeremiah was granted the license, previously held by Thomas

Haines, on 11 September 1880. In January 1882, he was found guilty of selling beer at an unlawful

hour on Sunday 1 January and fined 20/- including costs as it was his first offence. Later that same

month, Sarah Warren was found guilty of being on his licensed premises at an illegal hour and fined

15/-.

In February 1884, Jeremiah ‘went surety’ for Samuel Weycott who was the landlord of The West

Country Home at Bath Square, Portsmouth Point. Probably using a life preserver, Weycott had

‘dangerously’ wounded a butcher during a quarrel at The Ship Worcester, Broad Street, Point.

Jeremiah was described as a ‘beer retailer and agent’.

Ten years later, he was still at The Gem, slaking thirsts, but in 1891 he was lodging at 28 York Street,

Portsmouth and, although now in his seventies, he continued an insurance agent. One suspects that

he had stayed in this career from the 1870s as beer retailers often had a second occupation.

The Gem isn’t shown on this postcard, but it was just to the left of the public house shown above.

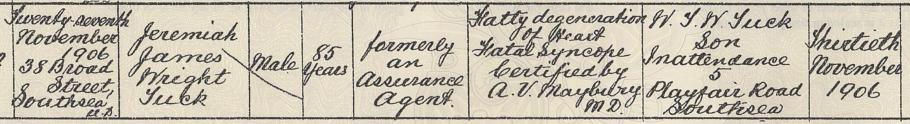

Jeremiah died on 27 November 1906, yards from the sights and sounds of the sea at 38 Broad

Street, Portsmouth Point (which was the famous The Blue Posts inn). He was eighty-five years old

and died from fatty degeneration of the heart which resulted in a stroke. His son, William was present

and gave his father’s occupation as ‘formerly an Assurance Agent’. Jeremiah was buried at Highland

Road Cemetery, Southsea.

Following Jeremiah’s death a brief obituary notice was posted in the Portsmouth Evening News:

‘A member of Foresters and Odd Fellows for upwards of 54 years’.

Jeremiah - The Oddfellow

Friendly Societies claim a beginning in Roman times - hence the name, ‘The Ancient Order of

Foresters’. They were formed to provide financial help to their members in times of want.

Subscriptions of a few pence a week were paid into a communal pot and from it were drawn sick pay,

unemployment relief, doctor’s fees, funeral expenses and widows pensions as needed. They were

self-managing mutual aid organisations.

The Societies varied in size from a few dozen members in small village clubs to giants such as the

Independent Order of Oddfellows which had four million subscribers in 1874. Many Friendly Societies

failed. If local work was seasonal, or there were times of mass unemployment or an epidemic, there

simply might not be sufficient funds to be distributed - another example of the greater security to be

enjoyed in numbers.

Meetings of Society ‘lodges’ or ‘courts’ were held every two or four weeks, often in public houses.

This arrangement was a sometimes a source of contention and resulted in the formation of the

Independent Order of Rechabites - their motto pointedly being, ‘Truth and Temperance, Love and

Purity’.

At their gatherings, subscriptions were paid and the Secretary reported on visits and payments to

needy souls who had been helped. Elaborate rituals at these meetings evolved - initiation

ceremonies, secret passwords and flowing regalia were introduced which confirmed the sense of

brotherhood among the members.

Some might find the names of these organisations to be a little eccentric - but they were deliberately

coined. The Oddfellows were formed by people who were unable to join other trade guilds – and

hence were oddfellows. The Foresters’ title is a reference to one’s journey through the ‘forest of the

world’ wherein all manner of dangers lurked. The Rechabites were named after the Biblical tribe who

renounced alcohol.

The main recruits for the Friendly Societies came from the vast ranks of the insecure working classes

and extra impetus to the movement in the nineteenth century was given by the grim alternative of the

workhouse in times of hardship. By the end of this century, there were 18,000 Societies with around

ten million members.

Their raisin d’etre was diluted in 1911 by the National Insurance Act which levied compulsory

contributions on all workers in return for welfare benefits. The Societies were still used by central

government to collect contributions and pay benefits. The coup de grace came in 1948 when the

system of state benefits was gathered under one umbrella and the services of Friendly Societies

were no longer required. Jeremiah may then have turned in his grave.

His attachment to Friendly Societies may give us a clue to Jeremiah’s character. He likely had a keen

sense of responsibility for the health and welfare of others. He appears to have been a sociable man

(remember, he had been a beer seller), perhaps revelling in the regular Society meetings and being

comfortable and persuasive when talking to strangers to convert them to the cause.

He would also have been literate and numerate, keeping records of subscriptions and payments. Of

course, he may have been an assurance agent simply as a means of making money! But the obituary

placed by his family surely speaks of fifty years devoted to the welfare of others - there is a certain

satisfaction to believe this of my great x2 grandfather.

One of my long-term goals is to trace a photograph of a great grandfather who died as relatively

recently as 1906.

Conclusions about Jeremiah

Of Jeremiah’s eldest son, James Jeremiah Wright Tuck

James Jeremiah Wright Tuck, Jeremiah’s first son, married Martha Robson in 1880 and followed his

father’s profession as a commission and insurance agent. The couple lodged at 8 Green Road,

Portsea in 1881.

Ten years later they had moved to Cheriton, Kent. While there, in 1891, James, working as a brewery

agent, made several agreements with tradesmen to supply the Honourable Artillery Company with

rations during their stay at Shorncliffe, Kent. This enterprise failed and he was sued in the County

County when judgment with costs was made against him.

Following this, James took on the Elm Brewery Tap in Portsmouth but stayed only five months and

then tried other business ventures but made ‘no headway in any’. As a result, he appeared at

Portsmouth Bankruptcy Court on 24 December 1892. He was an insurance agent living at 40 King

Street, Southsea and had a deficiency of £80.

Just before this episode, a twenty-year-old servant girl (with four aliases) was accused of stealing a

gold pencil case, valued at 30 shillings from James for whom she worked.

James and Martha had three surviving sons. In July 1899, there was an unfortunate court case

involving one of these. The family had a lodger who committed an act of gross indecency with him. It

was alleged that Martha Tuck approached the accused and offered to settle the case if he made a

payment to her.

As a result of James’ business experiences, 1901 found him working as a Dockyard labourer and

living with his family at 15 Brougham Street, Southsea.

Ten years later, in 1911, Martha was living at 4 Church Street, Southsea and working as a lodging

house keeper. James was living with his relatives, William and Mary Ann Bartlett, and was working as

a drapery commercial traveller . It emerged from the census that the couple had had ten children of

whom seven had died.

James died in the Southampton area in the spring of 1926 and Martha died the following year at

Portsmouth.