‘I want to keep my own individuality. I don’t want to be forced to do something I don’t want to do’

January 2002. Photographs dated, l to r: 1912; 1926; 1930, 1971, 2002

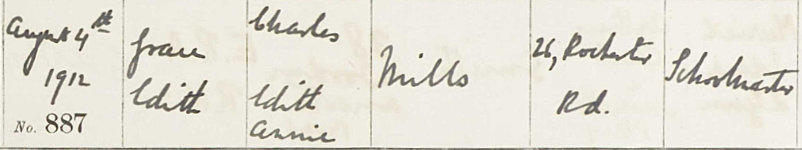

Grace Edith Mills was born in the year the Titanic sank (as

she often reminded us). This was possibly why ‘her ship

never came in’ which was the reason she gave later for our

modest standard of living.

She was the first child of Charles and Edith Mills (born 24

June 1912.) Her middle-class family was living in Rochester

Road, Southsea and, less than two years later, Grace’s

brother was born. Four months later the world was engulfed

by war. Charles immediately enlisted and was posted

initially to Longford Road, Bognor where Grace and her

family remained when Charles was sent to France.

School days and growing up

Baptism at St James, Milton, Portsmouth

In 1918, peace finally settled and so, soon afterwards, did the Mills family - at ‘Verona’, Ophir Road,

North End, Portsmouth. Grace was educated at Portsmouth High Schools for Girls. She forged close

friendships with two other girls at school, one of whom was Marjorie Brown. Grace kept several

photographs of the trio and when Marjorie died, more than seventy years later, Marjorie left Grace a

legacy in her will.

Grace showed a good turn of speed as a sprinter. When I was about ten years old, she entered the

hundred yards dash for parents and although she was well into her forties, Grace won! Her reward

was a box of chocolates - which cost less than her stockings which needed to be replaced.

During her youth, Grace, like so many middle-class children, learnt to play the piano. Unlike so many,

she persevered and played for the rest of her life - including accompanying her religious congregation,

often with no notice.

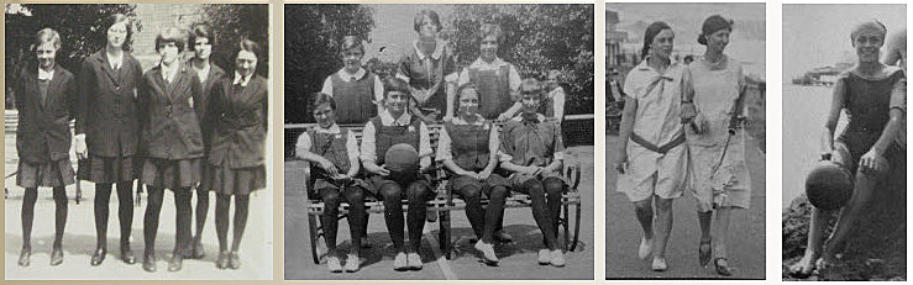

Grace is far left Grace is far right, standing Grace with her mother

A move to London

After Grace finished High School in 1928, she decided to study

Pitman’s shorthand. Although her father taught this subject, her

decision seems to have coincided with her grandmother’s need for

companionship as her husband had died four years earlier.

As a result, Grace moved from Portsmouth to Stoke Newington,

London, enrolled in a secretarial school and started work in London

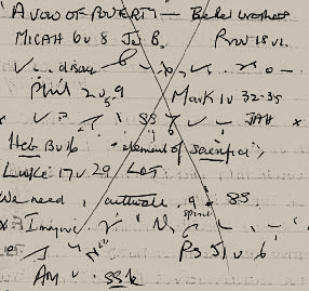

aged seventeen. As can be seen from the example (right), Grace’s

shorthand expertise evolved according to whether she could

remember the symbols or not! Nevertheless, she made great use of

her skill particularly when making notes during Bible talks.

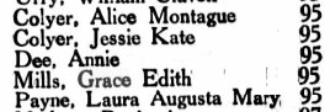

The electoral roll at Stoke Newington supports this account of her

movements because she is listed at her grandmother’s house, 95

Fairholt Road, from 1934 (when she was aged 21 and eligible to

vote) until 1937 (see right - Laura Payne was Annie Dee’s

companion and the Colyer sisters lived in a flat in the house.

However, Grace was not included in the 1938 listing).

Grace worked as a stenographer/assistant lady almoner at St

Bartholomews Hospital (“Barts” shown right) in the City of London,

not far from St Pauls Cathedral and about four miles from Stoke

Newington. The hospital has existed on the same site since its

founding in the 12th century, surviving both the Great Fire of

London and the Blitz.

It was around this time, when Grace was twenty-one, that, like her

mother, she became profoundly deaf. This impairment was to

blight, restrict and impact on her life - but more about this later.

The role of the hospital almoner was to organise after-care for patients, including stays in

convalescent homes, special equipment for use at home, additional nutritional needs and so on. At

the same time, they were expected to identify patients whose families were in a position to make

some financial contribution towards treatment. As the condition of hospitals improved, more people

were willing to use their services, and the almoner’s role was to ensure that those who could afford to

pay, did so. Almoners were thus expected to act as a go-between and ambassador for the hospital in

its dealings with patients’ families.

They were required to keep meticulous records on each case, and to negotiate with other Hospitals

and charities (as well as local authorities) for equipment, convalescent home places, and nutritional

supplements. The Almoners’ work involved an encyclopaedic knowledge of what was available within

the hospital and elsewhere for the benefit of patients. The almoners saw themselves primarily as the

intermediaries between the Hospital and the patients’ families. It was the almoner who offered

practical advice and guidance, and a sympathetic ear, to the parents of coeliac patients. It was also

the almoner who conducted delicate conversations with long-term patients, affected by limited contact

with their families, and it was the almoner who found the money for respite care, and for the transport

costs of cash-strapped relatives, so that they might visit as much as possible. As a group, the women

took a practical approach to a role in which they were faced daily with the practical difficulties of

having a sick child in the family. In the words of one almoner, “[Our] work is not designed to make life

softer but to help people cope with difficulties, changing in a constantly changing society.”

While not suggesting that Grace was personally involved in this work, as a stenographer, she was

more likely to have supported this aspect of hospital life by helping with the production and keeping of

records.

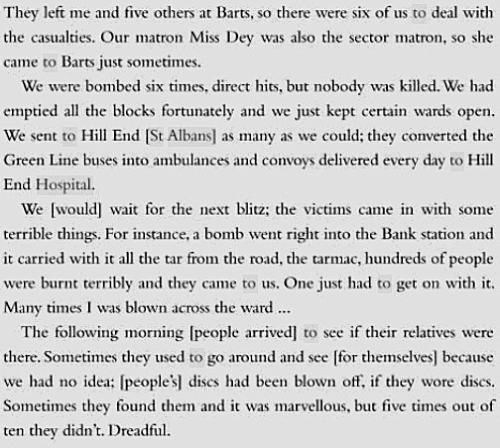

There was more upheaval for Grace. World war created the need to move Barts almost lock, stock

and barrell from London. Most of the nursing staff and patients were evacuated. In the first two weeks

of September 1939, 308 Bart’s nurses were moved to Hill End Hospital at St Albans. Throughout the

war the nursing staff had to nurse far more beds than was usual in peacetime. In 1938, St

Bartholomew’s Hospital had 763 beds, but in 1940 there were more than 1100 at Hill End alone, with

over sixty beds in each ward.

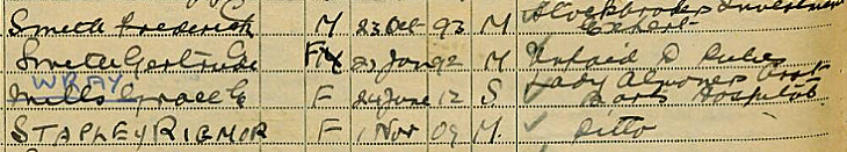

The 1939 Register noted Grace as Most of the nursing staff and patients were evacuated from central

London. In the first two weeks of September 1939, 308 Bart’s nurses were moved to Hill End Hospital

at St Albans. Throughout the war the nursing staff had to nurse far more beds than was usual in

peacetime. In 1938, St Bartholomew’s Hospital had 763 beds, but in 1940 there were more than 1100

at Hill End alone, with over sixty beds in each ward.

The 1939 Register noted Grace as being at 54 Salisbury

Avenue, St Albans (shown right). She was sharing digs with

the married Rigmor Stapley.Their landlord was the forty-five-

year-old stockbroker investment expert, Frederick Smith.

This was complete surprise to me. I had no idea she lived in

Hertfordshire at this time - and it explains why she was

assigned to a Hertfordshire farm when she joined the Land

Army. If war had not been declared and Grace had not been

working at Barts, I would never have been born.

Hill End, near St Albans

But even here, supposedly far from the ravages of war, the hospital was not safe:

Sisters: Memories from the Courageous Nurses of World War Two - Barbara Mortimer

But I am running ahead and should close the door on Grace’s life in London.

While in London, she enjoyed life in the metropolis. She attended the Proms at the Albert Hall,

celebrated the New Year at Trafalgar Square and knew her way around town. Much later she

took her children to Lyons Corner House (a place that clearly held happy memories for her) for a

special treat - high tea.

I know from her choice of godmother when I was born that Grace was a committed Anglican and

she was also possibly influenced by her grandmother who was a staunch churchwoman. Just

before her death, she spoke of the summer breaks she had enjoyed with the Church Holiday

Fellowship. She went to Austria with the Fellowship in 1937, Stonehenge and also enjoyed a

‘well organized trip’ to Conway Castle in Wales and ‘a trek up Snowdon’. The photographs taken

on these trips show that her school friend, Marjorie Brown, accompanied Grace.

About this time, her brother remembers that Grace had ‘an understanding’ with a clergyman who

promised to marry her. However, he went to South Africa and returned, a married man.

During this time she regularly spent summer holidays with her parents, as recorded by seeveral

photographs:

Grace (kneeling centre) and her school friend, Marjorie Brown (to her left) with the Fellowship

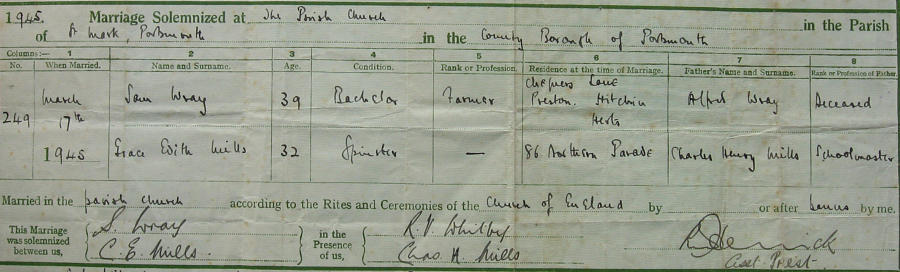

The Land Army

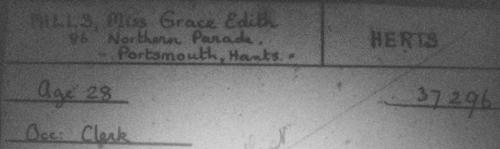

Then, World War Two cast its shadow over Britain. As Grace later put it, ‘You see, the war came

along and it meant that you had to do your bit. The forces wouldn’t take me as I jolly well couldn’t

hear so the only other alternative was the Land Army’. According to her filing card in the National

Archives below, Grace joined on 25 January 1941. She gave her occupation as, ‘clerk’.

That was how she found herself in winter-time ‘wearing wellingtons,

grading potatoes in the snow, with a tarpaulin over us in the middle of a

field in Hertfordshire -our hands were awfully cold’. She had landed at

Home Farm, Preston, near Hitchin.

The Woman’s Land Army was formed because tens of thousands of

country-men either enlisted or transferred to industry leaving a

desperate need to keep the farms running and maintain the supply of

food. It has been estimated that there were ninety thousand Land Girls.

Grace was No. 37,296.

When the world was turned on its head, the Land Girls learnt the equality which was thrust upon

them. Farmers tested them by assigning them routine, menial and back-breaking jobs such as

muck-spreading, sowing potatoes, cutting thistles before the harvest and topping and tailing

turnips. Working in the chill of winter and the summer’s heat, they battled against mud or dust all

year round.

The main challenge was keeping their femininity when dealing with with corns on their hands,

muscular arms and weather-beaten faces.

They were issued with a uniform (often the wrong size) which was alien to wear at first: breeches,

shirt and tie, long woollen socks and heavy brogue shoes. In some ways the clothes were a

blessing in those days of austerity and dwindling wardrobes.

Many found the biggest hurdles were the stench of the farmyard and how to take a natural break

when working in the fields during winter-time: searching for a sheltered spot far away from

masculine eyes and then peeling off several layers of clothes.

I’ve been told by a later owner ,that some of the Land Girls were boarded at Crunnells Green

House (pictured below) which was near Home Farm.

Even getting along with one’s work mates could be

challenging as Land Girls were plucked from all walks

of life - Grace remembered that there was a talented

artist in her group.

Yet after dwelling on the obstacles, many women have

fond memories of their life on the farm: the fresh air,

reasonable food (even in wartime), the camaraderie

and the local attractions which included....men! Enter

Sam Wray, farm labourer, stage right.

28 September 1943

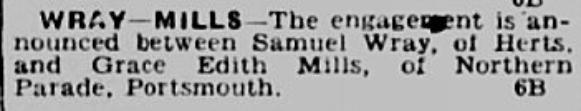

The marriage

Sam and Grace married in Portsmouth at St Mark’s Church, North End (above) on 17 March 1945

(she resigned from the Land Army thirteen days later on 30 March). She wistfully said, just before her

death, that ‘this ought to have been the outstanding day of my life’.

It seems to have been a low-key wedding. There is only one wedding photograph, in which Sam

seems stiff and ill at ease. He was probably conscious of the difference between his social standing

and that of his bride’s family. Indeed, in an evident attempt at parity he was fancifully described as a

‘farmer’ on the marriage certificate. His best man was his brother-in-law, Ron Whitby.

And Grace is not wearing a wedding dress in the photograph - rather an expensive ‘two-piece’. She

was to wear this for later photographs with her young children. We should remember that this was

after six years of world war. Austerity was the new vogue.

I don’t know who attended the wedding. Her father was present - and signed the certificate as a

witness. Incidentally, the signing by the witnesses is not genuine. It is certainly not Grace and Sam

who signed. rather, it’s probably Grace’s father, to cover the fact that Sam was not a comfortable

writer. Were Sam’s mother and Grace’s grandmother able to travel?

Grace’s brother did not attend - possibly because of his RAF commitments. Grace commented later,

‘Mum and Dad were very much against my marrying Sam, of course’.

Bearing in mind that she was thirty-three and distinctly on the shelf perhaps there was an element of

desperation in her decision. Sam was almost forty years old and unalterably fixed in his ways.

Several decades later, I heard several comments from Sam’s family and Preston villagers about the

marraige. One said, “(Grace) was a lady”. Another, “(Preston village was) not the right place for

her...you’ve got no business taking her there”. The consensus on both sides was that it was an

unsuitable marriage. Yet it endured. More than fifty years later, the couple were still together.

Married life in the Hertfordshire countryside

The couple made their home in a farm workers cottage, Reeve’s Cottage (left), in Sam’s home village

of Preston. The cottage was probably the oldest home in the village with exposed wooden

framework, low ceilings and rather cramped - or so it appeared to me when a modern-day owner

showed me around.

Without actually knowing, but imagining her feelings, although Grace was familiar with Preston and

knew some of the local folk, village-life after living in Portsmouth and then London must have been

hard to which to adapt. The cottage was almost a quarter of a mile from the neighbouring homes.

There was one shop in the village. The nearest town was three miles and a bus-ride away. Her

husband’s family were country people and his two sisters who lived locally had personalities which

wouldn’t have drawn Grace into the bosom of their family. Probably, she threw herself into caring for

her home and husband and found relative normality in the local country church.

It’s likely that Grace struggled to come to terms with her new life. She loathed Preston and refused to

return in later years.

Reeves Cottage in 1977 (left) and 2020. It appears neat and cared for - with its carefully

tended lawn and flower bed. I’ve seen a photograph of the exterior of the cottage a short

time after Grace and Sam lived there and it looked like a typical farm labourer’s home - a

little run-down, unkempt and small (without the extensions which have obviously been

added since). The property was sold for £1m in 2019.

(Left) a group of Land Girls at Preston. Grace is far left.

Back to Portsmouth

The means of escape came when Grace was expecting her first

child. Her son, Philip John, was born (far away from Hertfordshire) in

Southsea, Hampshire on 12 January 1946. Mother and son (pictured

right) remained in civilisation for eighteen months before returning to

Preston. They stayed with Grace’s parents.

When their second child, a daughter, Barbara Joy, was born (on the

Queen’s birthday - 15 April 1949), Sam bowed to the inevitable and

the family cut their rural ties and moved to Portsmouth permanently

to share the home of Grace’s father, a retired school master, who

was now a widower. Grace’s brother recalls an almighty row when

the family arrived at Portsmouth.

Grace’s conversion to being a Jehovah’s Witness

About a year later after Barbara’s birth, something happened

which Grace later described as the ‘highlight of her life’. She was

visited by two Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Grace had been a staunch member of the Anglican church -

indeed I can distinctly remember going regularly to Sunday

School and on summer outings organised by the local church.

She later said that what made her stop in her tracks was that she

was asked, ‘What does the Lord’s Prayer mean?’ Despite years

of church attendance, she found that she was unable to answer.

Further discussions with the two Witnesses ensued. Grace kept

the magazines that they left with her and on the front covers was

written first, ‘Mrs Wray’, then ‘Grace’, then ‘Sister Wray’ as her

interest grew and she was baptised into a new religion in 1952.

Right, Margaret Beagle who visited Grace with Molly (left) and

Margaret’s husband, Glen Howe (a Canadian lawyer who

fought many cases in his home country representing Witnesses

and fighting for their rights).

Her conversion created tensions in her family life and among her circle of friends. True to form, Grace

didn’t hold back from telling her relations and friends about her new views. One of her cousins (a

church organist) recounts that Grace sent him a copy of the New World Translation of the Greek

Scriptures. She probably sent similar gifts to several relatives, which went down like a ‘lead balloon’

with those who were set in their religious ways.

I find this deeply sad as Grace clearly loved her family (as evidenced by the many photographs she

treasured) and had strong bonds with them, but these were strained by her new and usually

misunderstood religious beliefs.

Also, her husband (who had his own agenda in the evenings) was antagonized by her religion, which

was considered by many to be an undesirable sect with extreme and controversial views. I recall

during one row that Sam, out of the blue and to Grace’s amazement, described the witnesses as

communists (a commonly-held misconception of the time due their their non-involvement in World

War II).

To fill the void in her life which was left by her disappearing family, Grace made several new friends

among the witnesses where she was a popular figure.

Sometime in the mid-nineteen fifties, Grace sat down with me to explain a further dramatic change in

her outlook. It is a belief of Jehovah’s Witnesses that, while an unlimited number of people will enjoy

future life on a paradise earth, they will be governed from heaven by a strictly limited group of humans

who die and are resurrected. Their number, they believe, is set at 144,000 in the book of Revelation

and is selected by God. A requirement is that they should remain as faithful Christians until their

death.

As there are seven million practicing Jehovah’s Witnesses, it might be thought that to be ‘called by

God’ for future heavenly life from such a vast number would be unusual and perhaps indicates

exceptional qualities.

Grace told me that she believed that ‘her hope for the future had been changed’ and that, following

her death, she was eagerly looking forward to life in heaven as one of the 144,000 rulers, rather than

life on a paradise earth. A consequence of this dramatic change was that her new hope dominated her

thoughts and life.

Making ends meet

There followed a time of struggling to make ends

meet. Grace’s father died in 1954. His estate was

divided equally between Grace and her brother,

Pat. She fought to stay in a semi-detached home

(right) that they could not possibly afford on the

paltry wages of a gas company ganger (who was

only happy when he had his beer, cigarette and

spending money).

In 1958, the family moved to the terraced 4

Beresford Road, North End (far right) which

Grace bought outright for £1525 - from her share

of her father’s estate. Sam (making no

contribution to the purchase) ungraciously

described it as ‘a rabbit’s hutch’. How Grace must have cringed on the few occasions that her

relatives visited her new home!

To make ends meet, Grace had a succession of menial part-time jobs - at Marks and Spencer, in a

pet shop and at a laundrette to which she would cycle. Her children were growing up and there were

the usual pressures between mother and offspring which were heightened by her husband’s

disinterest in family matters. Grace virtually raised her children on her own and inevitably there were

problems, particularly with her daughter, as Grace found it hard to deal with a world of changing

values. Despite this, Grace said later that she ‘enjoyed bringing the children up’.

Her two children left Portsmouth and married. Sam retired in 1971. Despite these changes, life for

Grace didn’t vary very much. She was absorbed with her faith: attending meetings three times a

week, studying the Bible and enjoying her house-to-house ministry. After Sam died in 1994, she lived

on her own bolstered by her friends. She spent time with her son and his family also her brother, who

was now living nearby at Bognor

Grace’s death

In 1996, Grace was diagnosed as having cancer of the colon. Part

of the offending organ was removed. When visited on the next day

at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Cosham she was amazingly sitting in a

chair with a cheerful smile on her face. She made a full recovery,

putting on weight and enjoying a good quality of life for five years.

Then, in September 2001, she fell heavily on the way to a religious

meeting and broke her elbow. This spelled the end as cancer took a

grip through her body and although miraculously experiencing no

pain, she died on 20 January 2002. Her children and brother had

assembled at her home and several members of her congregation

called to say, ‘Farewell’. She was cremated at Fareham Crematorium. For Grace, death opened the

portal to immortal life in heaven where she would be one of the ‘kingdom of priests’

Her brother described her as honest and sincere. He said that, like her father, she was outspoken

which sometimes worked to her detriment Many times after hearing about one of her conversations, I

would say to her, ‘But you can’t say that to people, Mum’ and she responded, ‘Well, I will!’. In that

respect and also if she found herself ‘in a corner’ she could be stubborn and intractable. Once she

had made a decision, it was ‘set in stone’ for better or for worse - which was certainly true of her

decision to marry Sam.

Once she had committed herself to such an incongruous marriage, she was resolved to fulfill her

responsibilities as a wife. However, her true feelings toward Sam can be gauged by her first will of

1967. She was the sole owner of 4 Beresford Road and she stipulated that if she predeceased Sam,

he could continue to live in the house, paying rates and insurance etc. But that if he did not keep to

the terms of the will or remarried then the house was to be sold and the proceeds equally divided

between Sam and her two children.

The first impression of people when they met Grace was that she was well spoken. Possibly because

of her deafness, her voice was powerful and many times I had to ask her to speak more quietly. She

liberally sprinkled her comments with middle-class vocabulary – ‘I jolly well will!’; ‘It hurt like billy-oh!’.

She was outstandingly enthusiastic, cheerful and outgoing in her manner. When answering the

phone, she announced her number with a lift in her voice. She answered the door when she was

expecting someone singing out, ‘I’m coming!’. Even bringing my breakfast in bed was a joyous event.

On the day before her death, she heard my sister and I talking about getting somewhere and she

burst into song, ‘Get me to the church on time’.

Grace lived to serve others uncomplainingly and worked hard to please people. Whenever I stayed

with her I left feeling guilty because I felt she had given far more than I had reciprocated. Sometimes,

her unreserved nature might drain her and she might become tired and a little short-tempered.

Grace - the person

She would hide her true feeling about people and events so as not to hurt

others feelings. Many was the time we discovered how she really felt about

something when overhearing her talking to someone else and her comments

did not tally with what we had been told.

Mealtimes personified Grace’s background. She was not ‘a Mrs Beeton’. Her

rock cakes and jam tarts which she persisted in cooking were memorable for

non-culinary reasons and she never mastered the art of cooking a fried

breakfast.

Yet she was fastidious in her presentation. Toast was always slotted into a rack, marmalade was

spooned into a special pot, serviettes were provided and even breakfast in bed was served with

teapot, milk jug and a basin of sugar. I believe this attention to detail reflected her upbringing.

Physically Grace was not especially feminine or delicate. She was left handed and slightly inclined to

clumsiness. She had broad shoulders and, when younger, she would tie back her shoulders with

stockings to try to prevent them becoming rounded. Even just before her death, it was an effort to lift

and support her.

In the interest of balance, I have to write that Grace’s daughter does not have a particularly pleasant

memory of her childhood at home. During her teenage years she feels that her mother did not deal

well with the vicissitudes of puberty and issues such as what clothes she could wear. She recalls that,

‘Mum was never there for me’, and that she was ‘left to her own devices’ or ‘given chores to do while

Mum was out preaching’.

Their relationship was marred by Grace’s religion which her daughter rejected when a teenager. I

also sense that Grace was inclined to favour boys more than girls. Having mentioned this, as a

testament to her sense of right and wrong, Grace left her estate equally between her two children -

which was much to her daughter’s surprise.

Grace had a ‘blind-spot’ when it came to remembering names of people and places. If she wanted to

recall an area she visited, she would note it in a diary and when meeting people after a period of time

she would go through their names before-hand - and then still get them muddled. The sort of typical

mistake she would make would be to call Winston Churchill, William.

She had a good sense of humour. If something tickled her, she was uncontrollable, silently rocking

with laughter until tears came into her eyes.

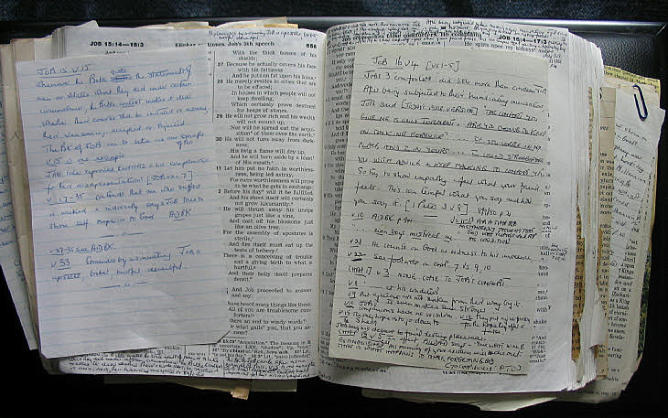

I have described her religious faith and commitment. She was an

exceptionally keen student to the point of obsession - constantly making and

keeping notes. When one Bible was worn out, she would painstakingly copy

all her notes into a new copy. Her last Bible was swollen with many sheets of

notes which she compiled from lectures and articles (see below). After her

death several people asked for her Bible as a keepsake.

My overwhelming memory of Grace is of a caring, selfless and vibrant mother

who was not without her faults but these were dwarfed by her empathy and

kindness.

Postscript

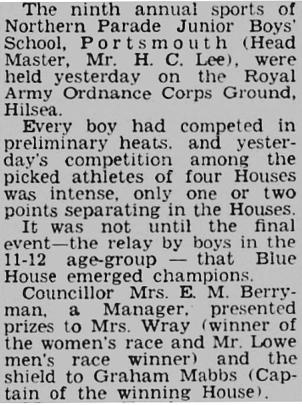

A few years ago I wrote an autobiography in which I described Grace winning a race at my Junior

School Sportsday. She was given a prize of a box of Milk Tray chocolates - which didn’t compensate

for the stockings she ruined during the run. I found this reported in the Portsmouth Eveneing News

Jun 1954, when she would have been forty-two years old:

In around 2005 (and out of the blue) I received a cheque from the Prudential Assurance Company for

£1,565. It was an unclaimed amount for an insurance policy that Grace had taken out on 18 February

1946, a month after my birth, which had accrued compound interest. She had religiously paid premiums

of 3½ d a month

Top

Grace and her grandmother

at Stoke Newington in 1935

1937

My maternal ancestors

My mother: Grace Edith Wray (nee Mills)

Site map