My maternal ancestors

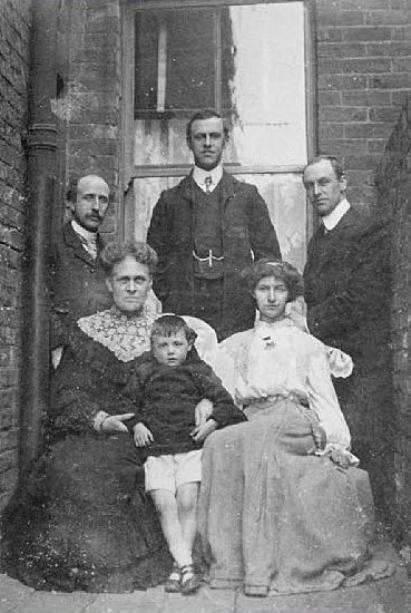

My great grandparents, James and Rosina (nee Tuck) Mills

1909c left to right standing: James, Archie and Charlie Mills,

seated: Rose and Eadie Mills with Fred Woodnutt

James John Pafford Mills was born within yards of the sea at Portsmouth Point on 14 March 1852.

His parents, James John (a seaman rigger) and Harriett (nee Lemmon) were both from seafaring

families and had married seventeen days earlier. He was brought up amid the sights and smells of

the infamous slum of Portsmouth Point surrounded by his close family. In 1861, the family were at

3 Blakes Yard and in 1871 Jame was with his grand-parents at Inner Camber Quay. He was an

apprentice shipwright at the nearby Portsmouth Dockyard.

Portsmouth Dockyard had a workforce of 4,000 in 1870. Among its elite hierarchy were the skilled

shipwrights who made up around a third of the workers. They were apprentice-trained and sufficiently

adaptable to work on metal shipping as shipbuilding evolved from the wooden hulls of yesteryear.

In the final analysis, not only sailors’ lives, but Britian’s survival depended on the quality of the work of

shipwrights. Because of this mindset, the pace of their work was ‘measured’ or ‘steady’ – some even

said lazy or slothful.

Shipwrights were divided between the ‘hired’ and the ‘established’ men. The quota of ‘established’ men

in the dockyard was fixed annually by Parliament’s Naval Estimates. Their numbers fluctuated,

reflecting whether or not war was imminent. ‘Hired’ men hopefully waited their turn to become

‘established’. They then had a slightly higher rate of pay and could look forward to a pension. This was

collected by retired wrights and was a visible reminder of the benefits which awaited the current

‘established men’ later in life. Established shipwrights were also guaranteed work no matter whether

any emergencies looked, or not. Few shipwrights were therefore to be found in the workhouse. They

also enjoyed paid holidays, paid sick leave and free medical attention.

Re: shipwrights

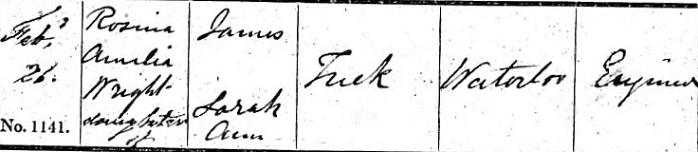

Rosina Tuck

Rosina was baptised at St Marys, Lambeth, London on 26 February 1858 when her parents were

living at Waterloo. Her father, Jeremiah James Wright Tuck had once been a seaman like his father.

By the mid-1860s, the Tuck family were living at Portsea, Hants and in 1871 they were a few doors

from a gate to Portsmouth Dockyard at 3 Chapel Row. Do we sense that a meeting of two young

people is about to happen?

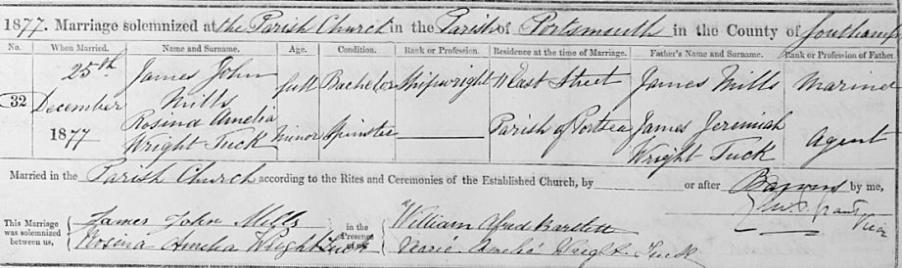

Marriage and children

James and Rose (aged eighteen) married on Christmas Day, 1877 at St

Thomas’, Portsea (right). This church’s outline dominates the outline at

Point and features in many photographs.

Rose was following a trend set by her sister, Maria Ann Maria, who had also

married a shipwright (William Bartlett) four years earlier. William was a

witness at the wedding - and likely was James’ best man.

In March 1879, the first of three sons, James William, was born, quickly followed by Charles Henry

(19 July 1880) and Archibald John in late 1882.

Their homes

The newly-married couple dropped anchor at 7 Waterloo Street, Southsea (cost £200c) which was

part of a newly-built housing project designed for Dockyard artisans.

The family was living at 7 Great Southsea Street (below, left) in 1891 (with Rose’s brother, William

Tuck, as a lodger) and had moved again ten years later to 51 Lawrence Road, Southsea (right). There

is a decorative brick that announces that this terrace was built in 1894, so James and Rose were

probably the first owners of the house. This was their last move and their five-roomed house

represented a gradual improvement in the quality of their home.

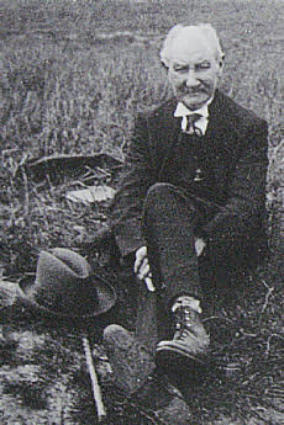

Of James and Rosina

James and Rose (pictured disapproving, above) showed great kindness to the

young boy shown with them in the photograph at the top of the page. His name is

Fred Woodnutt. My mother recalled that he was an ‘adopted’ son of James and

Rose and that he later married and moved to London.

I have discovered that Fred was actually the son of James’ sister, Harriet Mills, who

married George Woodnutt. Fred was born towards the end of 1901 and Harriet died

the following summer. It appears that James and Rose generously took him into

their family shortly afterwards.

James and Rose were becoming more and more proud of Charles and Archibald who were forging

promising careers in teaching. Charles attended Hartley University College at Southampton and

achieved a first class degree. In 1909, he married a fellow student who was the daughter of a

prominent London business man and councillor. Of the Mills family, only Rose and Archibald

attended the wedding. James detested travel. Rose (who had to be persuaded to attend) looks

distinctly uneasy (see above right) in the wedding photograph: possibly conscious of the social divide

between herself and her in-laws.

After seeing Charles return unharmed from World War I and continue teaching and Archibald

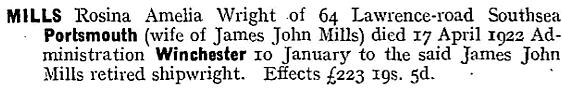

appointed as headmaster of the Beneficial School, Portsmouth, Rose died from leukaemia on 17

April 1922 at the relatively young age of 64. She was buried at Highland Road Cemetery, Southsea.

Her estate was valued at almost £224.

Her grandson remembers her as being very kind, quick-tempered and blunt. She rarely smiled. She

was ‘manly’ and adventurous even ‘going up in an aeroplane’ shortly before her death. She

undoubtedly ‘wore the trousers’ in her household and her husband was subservient to her.

After her death, James moved across the road to 64 Lawrence Road and lived with his son, Archibald

and his wife, Nellie. He visited Charles and his family every fortnight.

James died, aged 84, on 19 November 1936 at St Mary’s Hospital, Portsmouth and was buried near

his wife. He died intestate and left an estate worth £363 8s 2d.

A grandson recalls that he was, ‘a small man, deaf and totally bald with clenched hands which were

malformed’ (presumably from his shipwright work). He was ‘lackadaisical and ran to work in the

Dockyard - if he was late, he wasn’t allowed in’.

Addendum

During a visit to the National Archives, while killing time before the coach left for home, I browsed

James’ details into the catalogue and was pleasantly surprised to find a document which related to

James’ work.

An incident in around 1 October 1909, and its repercussions, provides us with a detailed insight into

James’ career. He was working on board HMS Neptune (shown below), a dreadnought battleship

which was laid down in January 1909 and launched on 30 September of that year. She was to be the

flagship of the Home Fleet from May 1911 until May 1912.

If these dates are accurate, Neptune was floating in Portsmouth Harbour – which may account for

James’ accident. He was working on bulkhead stiffeners in the ship’s bunkers when he fell on the

edge of a plate and broke two ribs on his left side. This injury was to plague him – although the ribs

healed and there was no damage to his lungs, he was unable to lift heavy weights. Almost four years

after his fall, he still suffered with ‘intercostal neuralgia’ on his left side.

As a result of this permanent injury incurred at work, James was awarded an extra allowance of 3/6d

a week. However, in 1917, this was suspended as he came out of retirement due to ‘the present

stress’ (ie WW1!) and was working. He appealed against this decision and this was upheld because

the allowance was small and the permanence of his injury. Details of his appeal can be found at The

National Archives and they include a potted history of his work in the Dockyard.

Remember that James and Rose married on Xmas Day 1877. Then, he began work as a ‘hired’ man

on 18 February 1878 when he was 25 years old.

There appears to be gap in his employment record. He was born on 14 March 1852. He likely

became apprenticed when he was fourteen years old in 1866 and his apprenticeship lasted seven

years – or until 1873 (in the 1871 census, he was described as a ‘Dockyard Apprentice’). If he started

working as a ‘hired man’ in 1878, what was his occupation between 1873 and 1878 – or did James

start his apprenticeship late? He was later to say that he worked in the dockyard for thirty years –

which may imply that he was not in the yard before he began work as a ‘hired’ man.

James was earning between £1 7s 0d and £1 10s 0d a week. But he was laid off on 7 September

1878 for more than two years until 20 December 1880. This must have been a worrying time for the

newly-married James and Rose. There was the mortgage to pay on their house which cost £200; their

first son was born in the late Spring of 1879 and my grandfather was born on 19 July 1880, when

James was still not a ‘hired’ shipwright. Did he find alternative work as a labourer in the Dockyard?

He was employed again from 20 December 1880 until 28 January 1899. Then, he was elevated to

being an ‘established’ shipwright from 29 January 1897 until he retired on 15 March 1912 – a little

more than fifteen years. His weekly wages were between £1 12s 6d and £1 13 s 0d until he had a pay

rise to £1 14s 0d on 1 October 1906.

James later declared, ‘I can honestly say that the thirty years I laboured in HM Dockyard were used

with a keen sense of duty’. His manager went on record as saying that James ‘discharged his duties

with diligence and fidelity and to my satisfaction’. He was recommended for the Imperial Service

medal. Despite James’ accident in 1909, between 1903 and 1912, he had not been absent from work

for a period longer than twelve days.

His total annual pension was a little less than £119 – the loss of his 3/6d weekly allowance mentioned

earlier, represented a reduction of almost 20%. No wonder he wrote that this money was, ‘essential to

me in the maintenance of my wife and family and its reduction would entail a hardship’. In 1917, his

earnings from his temporary private work were £3 10s 0d a week.

One further point of interest is that James signed himself James John Pafford Mills. This indicates his

awareness of his family background and desire to acknowledge the Pafford name. Of course, he

knew his grandfather, James Pafford/Mills, who died when he was twenty-seven years old.