My maternal ancestors

The Tuck family of Norfolk

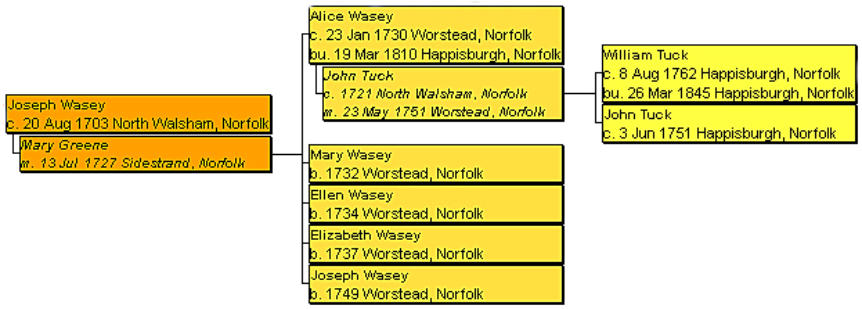

In the eighteenth century, the Tuck branch of my family were living within a triangle in Norfolk formed by

Cromer and Yarmouth on the coast and Norwich, inland. I begin with my greatx5 grandparents, John and

Alice Tuck - although possibly one can trace Alice’s family back a few more generations, albeit with

uncertainty

John and Alice settled initially at Worstead, a small parish six miles inland and south-west of Happisburgh.

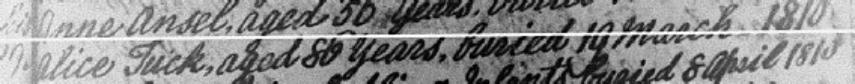

(Link: Happisburgh to do) However, Alice was apparently living at Happisburgh when she died in 1810 (see

below) - possibly living with one of her children

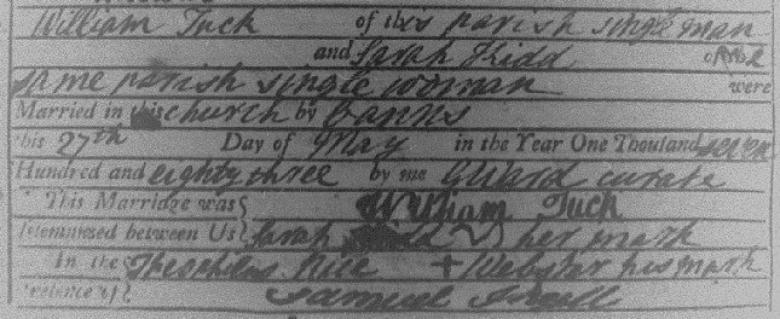

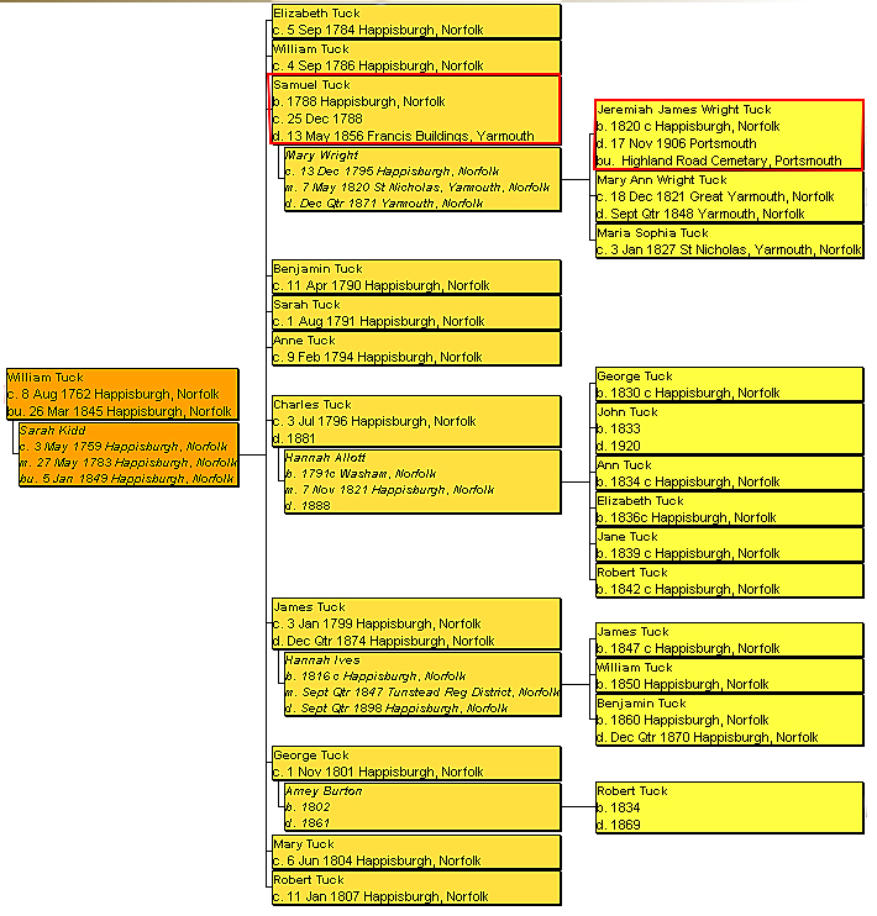

My greatx4 grandparents - William and Sarah (nee Kidd) Tuck

The parish records and censuses of Happisburgh reveal more than the basic details of William and

Sarah’s baptism, marriage and burial and information about their children. William was literate, while

Sarah merely marked the church register. They struggled to make ends meet - William worked as a

fisherman - one of only four at Happisburgh in 1841. He was almost seventy years old at the time,

while the other three were aged between 25 and 30.

William and Sarah’s marriage record - 27 May 1783

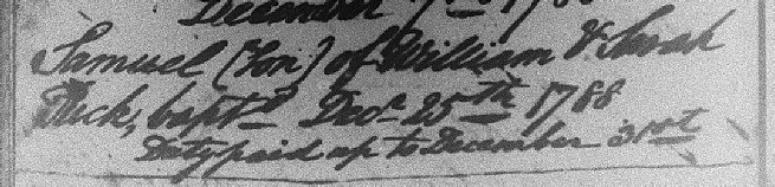

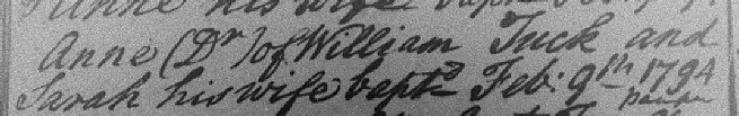

Shown above are the baptismal entries for William and Sarah’s children, Samuel and Anne. Anne’s

record notes that William was a ‘pauper’. Her sister Elizabeth’s baptismal record has the comment,

‘prio pauper’ or previously pauper.

Clearly this provides an insight into the financial circumstances of the family in 1784 and 1794.

However, there is more to this entry than meets the eye. In 1783, the Stamp Duties Act was passed

whereby all baptism, marriage and burial entries in the Parish Registers were subject to a tax of 3d.

The monies collected paid for the American War of Independence. There is a note on the copy of the

Baptism Register for 1788 shown above that the duty was paid on the entries for that year. Paupers

were exempt from this levy. The tax was unpopular and rescinded in 1794. Some clergy were

sympathetic to the plight of the less well-off and ‘stretched a point’ when recording events so that

families were spared the tax. Was this the case with the Happisburgh clerk? Probably not. In 1793,

for example, there were twelve baptisms recorded but only three parents were noted as ‘paupers’.

Of William and Sarah’s twelve children, two had the reference to pauperism inserted when they were

baptised. If William was a fisherman at this time, perhaps this indicates the seasonal nature of a

fisherman’s earnings. The huge shoals of herrings only passed nearby from September to December.

Suffice it to say, William and Sarah were poor.

The fisherman’s lot at Happisburgh

As well as the prolific herring catch, oyster beds were discovered off Happisburgh in 1820. However,

fishing in the North Sea and danger are synonymous. The rip tides and unpredictable winds combine

to create a most inhospitable working environment.

Happisburgh together with its coastal neighbours conspired to form underwater hazards. Their cliffs

fell regularly into the sea, creating off-shore sandbanks so dangerous that two lighthouses were built

and became operational in 1791. They were augmented by a lightship in 1832.

There were compensations. In 1868, mammoth’s teeth, hitherto buried inland for millenia, were found

in fisherman’s nets. And the twin-threat of vicious tides and gales both of which, in a moment, could

cast vessels onto the sandbanks or the beach could also be a blessing. They provided the opportunity

for salvage - and a reputation for heroism when the fishermen put to sea to rescue the crew of

foundering ships. Indeed, the news from the area in the nineteenth century is dominated by accounts

of shipwrecks, loss of life and acts of valour by Happisburgh fishermen.

For example, in October 1814, the William was ‘totally lost on Happisburgh Sand; the crew were

picked up by a fishing boat....the next day a laden collier struck upon the same sand which with

immediate assistance and throwing some of the cargo over, was towed off towards Yarmouth’.

Eight years later, the Sophia Magdalena struck on the sands. She was boarded by Happisburgh

fishermen who ‘attended her for some days and brought away part of her cargo; but this was

attended with the risk of their own lives and requiring great exertion the vessel sometimes being 12 or

14 miles from land.’ When a gentle sea breeze sprang up, two attending boats were able to tow and

beach her.

In 1826, the Thetford was blown ashore at Happisburgh and two local fishermen helped save the

crew and a female passenger for which they were nominated for their ‘meritorious conduct’.The

following year, a large brig was seen on the sands with her hull under water. There was no sign of life,

so the beachmen of Happisburgh went out to salvage what they could from the wreck. They found the

crew hanging on the rigging but a high tide scuppered their rescue attempts. They made a few

passes but were unable to pick up anyone and the ship broke up and its crew perished.

Then, in 1829, a two-masted herring boat was driven on shore at Happisburgh. As the tide went out,

‘the venturous and humane fishermen waded towards the ship and hailing her, received the joyful

tidings that all were safe.’

These examples from between 1814 and 1829 have been selected as they may well have involved

the fisherman, William Tuck. In 1841, there were only four fisherman recorded in the census. They

included William, now almost seventy, and three men aged from 25 to 30 years

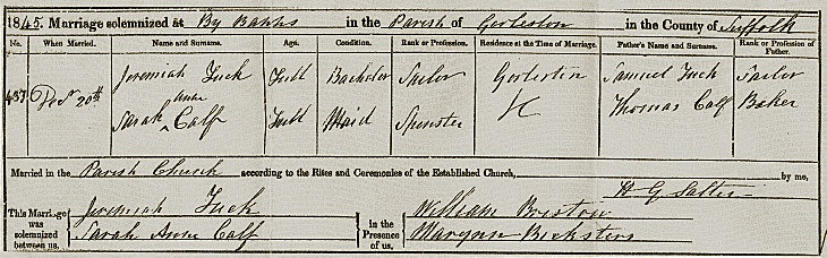

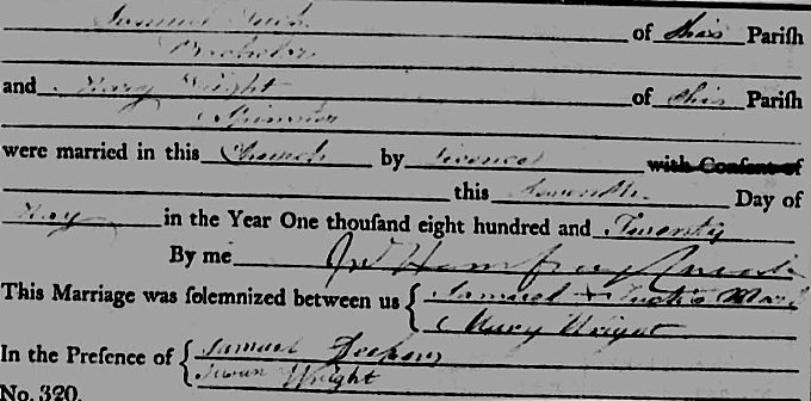

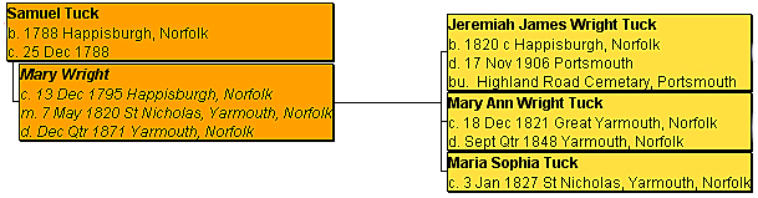

My greatx3 grandparents - Samuel Tuck and Mary (nee Wright)

The only way of making a positive connection between Samuel Tuck and my confirmed ancestor,

Jeremiah Tuck, is the Jeremiah’s marriage certificate (reproduced below)

Samuel Tuck was baptised on Christmas Day 1788. He married Mary Wright (Link: Wrights) at Great

Yarmouth on 7 May 1820. Samuel marked the certificate, while Mary signed with an accomplished

hand. Their marriage was announced in the Norfolk Chronicle.

Samuel and Mary had three known children, though I suspect there are more waiting to be

discovered.

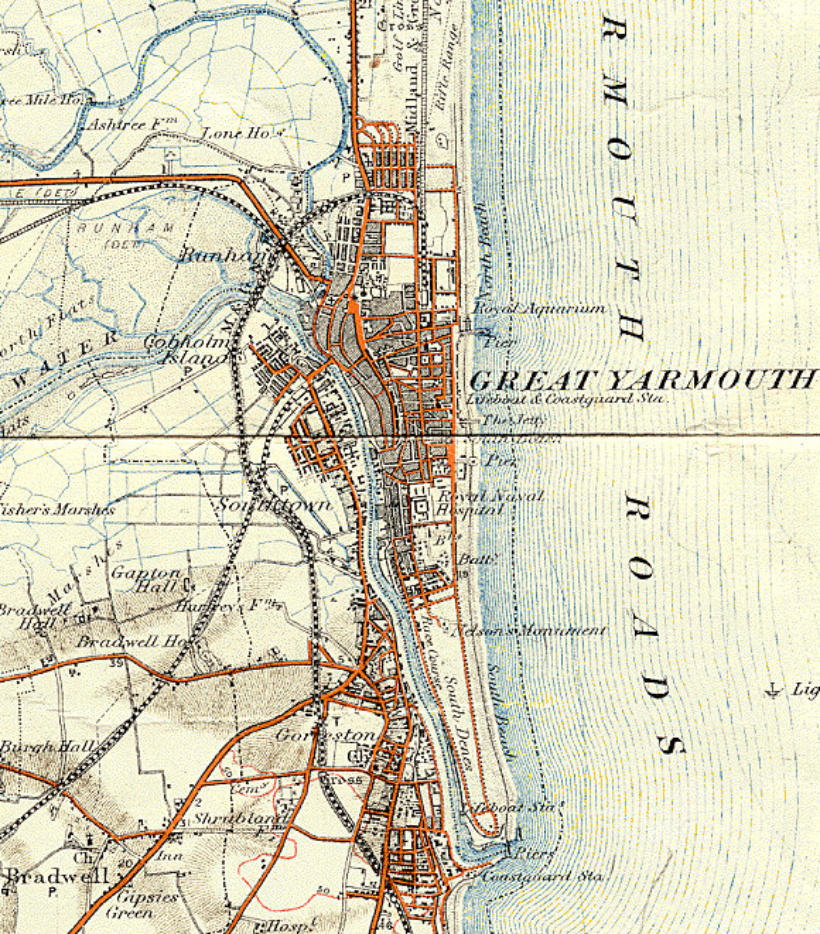

As befits a native of Happisburgh, some of Samuel’s occupations had a connection with the

sea. In 1841, he was a shipwright (the first of several in my tree) and he was living with his

family at High Street, Gorleston - a close neighbour of Great Yarmouth to the south, and in the

county of Suffolk (see map below).

When his son married, Samuel’s occupation was noted as sailor. He was in the merchant (not

the royal) navy and there is a record of his maritime service at The National Archives: he was

on board the Intrepid in October 1843 and June 1844. There is a news report concerning the

lugger (a small working boat with a lug-sail) Intrepid at Yarmouth in 1849 which may or may

identify the type of vessel on which Samuel served.

Fishing boats in a breeze outside Yarmouth

In April 1847, Samuel together with Robert Kirkby and John Hodge were found guilty of smuggling

eight pounds of tobacco, seven pints of Holland gin and five pounds of tea on the cutter, Nancy (A

single-masted, fore-and-aft-rigged sailing vessel with two or more head-sails and a mast ). He was

fined 7s 6d and costs.

Perhaps this episode ended Samuel’s sea-going career as four years later, in 1851, he and Mary (a

nurse) were living at Francis Buildings, North End in Great Yarmouth (see map below) and Samuel

was working as a carter - an occupation defined later as a coal carrier. Also present in the household

was the widower, William Bickers, (who had married the Tuck’s daughter, Mary Ann. She died in

1848) and their grandson, William Bickers jnr.

Samuel (67) died at Francis Buildings on 13 May 1856 from ascites - the accumulation of fluid in the

abdominal cavity. Eighty percent of ascites is the result of advanced liver disease or cirrhosis.

In 1861, Mary was still at Francis Buildings with her brother, James Wright and grandson, William. Ten

years later, she had moved to Wallers Buildings (see map below) at Great Yarmouth where she had

her grandchildren, William and Ellen Tuck, for company. Mary died towards the end of that year, aged

seventy-five.

Of William and Sarah’s children

When attempting to trace what became of William and Sarah’s children, several prove elusive. And

there may be another to be added to the list - Charlotte Tuck, aged around 35, was living with them in

1841.

Charles Tuck (born 1796) married Hannah Allot at Happisburgh on 7 November 1821. A witness to the

marriage was his brother, Benjamin Tuck. The couple had at least six children as set out above. In

1841, Charles was living at Happisburgh and working as an agricultural labourer. He doesn’t feature

in the 1861 census and died at Balcotha, Otago, New Zealand on 1 October 1881, aged 89.

Robert Tuck (born 1807) appears fleetingly at 11 Thornton Street, Southwark, London where he was

living on his own, a widower and a hairdresser. He died in early 1882.

James Tuck (born 1799) was living alone at Happisburgh in 1841 but was a neighbour of James

Wright (born 1783). In April 1837, there was a sale of two cottages and a shoemaker’s shop which

were occupied by John Hemp, James Wright and James Tuck. The latter was working as a

shoemaker in 1841. This may indicate a closeness between these families.

James (48) married Hannah Ives (31) in the summer of 1847 and was working as a fisherman in

1851. The couple had three known children and their son, William was also working as a fisherman in

1871. However, in 1861 and 1861, James was a farm labourer.

James died towards the end of 1874. Hannah was a midwife at the Swan Inn, Wimpole Stree,

Happisbirgh in 1881 and died in the summer of 1898.

Wallers Buildings and

Francis Buildings

High Street,

Gorleston