My maternal ancestors

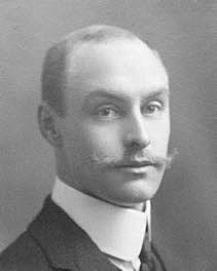

My grandparents: Charles and Edith “Eadie” (nee Dee) Mills

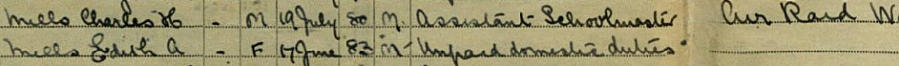

My grandfather, Charles Henry Mills (“Charlie”), was born on 19 July 1880

He was the second son of a skilled and qualified shipwright who was

employed at Portsmouth Dockyard. The Mills family were living at 7 Great

Southsea Street, Southsea which was part of a development of Georgian

and Victorian streets built to house dockyard craftsmen and workers.

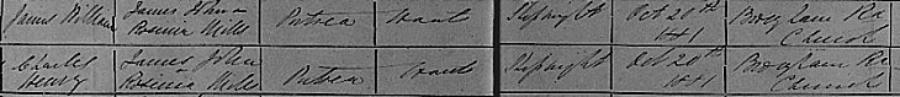

Fifteen months later, Charlie was baptised along with his older brother,

James, at the Bible Christians church (later, a United Methodist church),

Broughham Road, Southsea (shown right) on 20 October 1881 (Possibly

this choice of church does not reflect his parent’s religious convictions but

was simply a convenient religious building as it was situated just over a

quarter of a mile from their home. Charlie’s younger brother, Archie, was

baptised at the Garrison Church - “The British Military Cathedral” - which is

near the seafront and about the same distance from Great Southsea

Street. It is notable because much of the bomb damage inflicted during

WW2 has not been repaired - it is now a roofless ruin)

By the turn of the nineteenth century, the Mills family (probably

driven by Charlie’s mother, Rose) had climbed a rung or two of

the social ladder and had had moved to 51 Lawrence Road,

Southsea.

Charlie was educated at St Lukes School, Landport, Portsmouth

which was near the City’s Guildhall. He was to be a student or

teacher at this school for about fifty years. In December, 1891

Charlie gained a certificate for proficiency in shorthand at St

Lukes. Then, during successive years between 1892 and 1894,

Charlie was one of the principal characters in the school festivals

which were performed to capacity audiences in the Guildhall’s

Great Hall. In 1892 he was the Beadle’s attendant in the cantana,

Idle Ben. The following year he played Sancho Panza in Don

Quixote -sprinkling the play with witty comments and ironic

proverbs. In 1894, he was the policeman in Dan, the Newsboy.

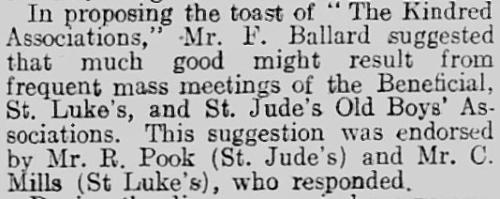

Charlie had taken the first steps along his career path - he was a

monitor on probation at Albert Road, Southsea School in 1894

and an assistant schoolmaster from 1898 until 1903 at

Portsmouth’s Beneficial School. His brother,Archie, was also a pupil teacher in 1901.

There had been some signs that part of the Mills persona was the ability to instruct: Charlie’s

grandfather, James Mills, had given ‘tuition for young gentlemen’ on HMS Asia in Portsmouth Harbour

and Charlie’s maternal great grandmother was a school mistress in London in 1851.

To improve his teaching qualifications from 1903 until 1905, Charlie attended Hartley University

College, Southampton from which he emerged with a first-class degree and a new fascination - he

was enthralled by a fellow student, Edith Annie Dee, who was affectionately known as ‘Eadie’ (a

name derived from her initials)

Eadie, however, was of a different social standing. Her father, George

Dee, was a business man at Stoke Newington, London who owned a

chain of small shops selling hardware products - what we would call DIY

goods.

George was also a local councillor who had been offered the mayorship of

Stoke Newington on more than one occasion.

Eadie was born on 17 June 1884 at Clapton, north London, the eldest of

four sisters. One of her sibling’s husbands was later knighted and another

received the CBE – which is a taste of the circle in which the Dees moved.

Like many young, middle-class ladies, Eadie also entered the teaching

profession, being a pupil teacher in 1901.

She enrolled at Hartley College in 1903. Why Eadie went to Southampton

to continue her training when there were several similar colleges in

London is, perhaps, hard to understand.

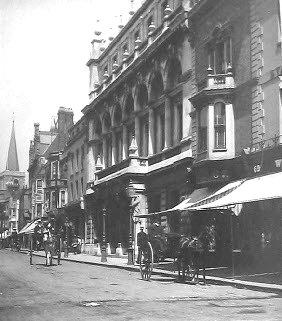

Hartley University College

The Hartley Institution was founded at High Street, Southampton

(right) by Henry Robinson Hartley in 1862. Today, it has evolved into

Southampton University but in the 1890s there was a serious need

for re-organisation of the institution. When Eadie and Charlie

attended the college, it had become a ‘technical college of the first

rate’ and had been renamed 'Hartley University College’ on 23

November 1902. The college’s motto was ‘Strenuis ardua cedunt’

or, ‘The heights yield to endeavour’.

As well as day and evening classes, from 1896 the College ran

courses to help pupil teachers to attain the certificate of teaching.

There were 130 pupil teachers in 1896-97 at the college and 200-

300 uncertified teachers in part-time attendance. Several of Eadie’s

friends were pupil teachers in 1901. There was no corresponding

college at Portsmouth which was the reason that Charlie went twenty-six miles along the coast to

Southampton. Hartley attracted students from Southampton, Portsmouth, London and Wales. On St

David’s Day, Common Room reeked with the smell of roasted leeks.

Eadie was living at 6 Carlton Crescent – in a ‘dignified residential district’

of Georgian houses - together with nineteen other students under the

oversight of a supervisor who viewed them as ‘cherished chicks’. Her

closest friends were “Bella’ Jeffries and Jeannie Forrest. There were strict

limitations placed on the social interaction between male and female

students. Each term saw ‘half-a-dozen functions (called soirees) that

included music, games and dancing’. Girls could only attend these if they

were chaperoned. They were not allowed out without permission after

6.00 pm in wintertime and 8.30 pm in the summer and had to be in bed by

10.00 pm. They were also forbidden to converse with male students

outside of the college precincts except when at recognised events.

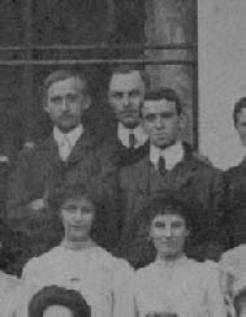

Right: Part of a group photograph of Hartley students. Charlie is at

the rear and Eadie is the girl on the left. ‘Bella’ Jeffries is next to her.

In the autumn of 1903, Edith was caught up in a controversy which centered on her digs at Carlton

Crescent.The matter was debated in two whole columns on a page of the Hampshire Advertiser. The

esrtablishment was evidently a hostel for Catholics, although Eadie’s family were Anglicans. The Rev

Mother of the hostel wrote to Hartley College saying that if any of the students who were living in the

hostel were dissatisfied with the treatment they had received, or wished to leave for any reason,

though sorry, she would not object to their doing so - provided this was sanctioned by the Board of

Education and arrangements were made to re-imburse the hostel for the ensuing financial loss. She

added that all students had come to the hostel with the consent of their parents and the full knowledge

that it was under her control.On 20 October 1903 an open letter was written which avowed that, ‘We all

wish to tell you we are exceedingly happy and comfortable at this hostel and have not the slightest

desire to reside elsewhere whilst pursuing our course of training at the Hartley University College’. It

was signed by all the residents including Edith A Dee and several students who appear in her

autograph book.

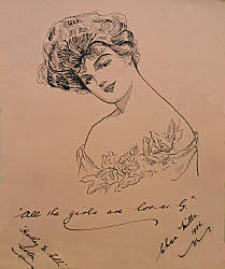

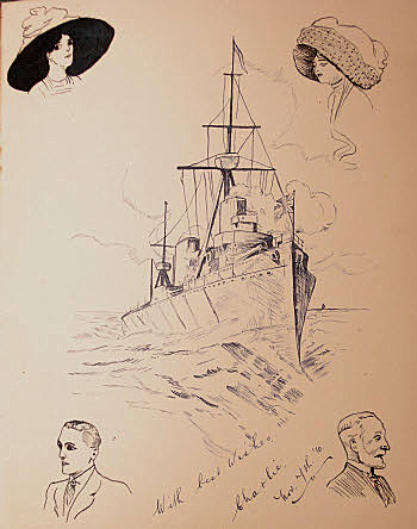

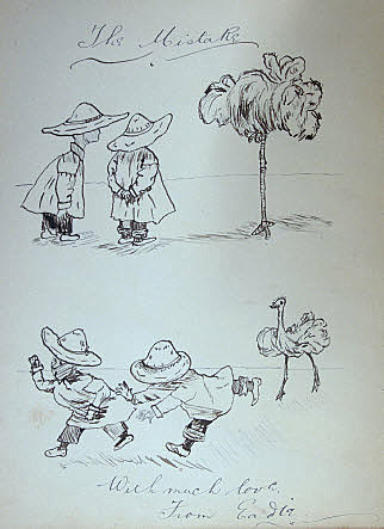

Eadie’s Autograph Book

From 1901 until 1910, Eadie kept an autograph book in which her fellow-

students and friends contributed drawings, poems and other pieces. It

provides a fascinating insight into student life in the early twentieth

century.

The book also shows Charlie’s evident interest: as well as a pencil

drawing of the bar-gate at Southampton, he also penned a portrait of an

anonymous young vamp with the caption: ‘All the girls are lov-er-ly’ (shown

right). This overt sentiment was quite different from the contributions of

other young men, although there may be an entry from Charlie’s brother,

Archie Mills, in the book – the author signs him (or-herself) A M s – which

maybe indicates that Charlie had a rival for Eadie’s affections

The courtship

Charlie began teaching at St Lukes School,

Portsmouth on 28 August 1905 and also taught

at the school’s Evening Institute. Eadie

returned to London where she probably taught

at Daniel Street School, Stoke Newington

(there is an entry in the autograph book which

reads Daniel Street School 1909).

Would Charlie’s feelings for Eadie wither

because of the distance between them socially

and geographically – Stoke Newington being

about seventy-five miles from Portsmouth?

Charlie was an active man. He swam regularly, coached the school football team and cycled. It was

quite possible to pedal to London and back spurred on by the fuel of ardour. However, on his arrival,

probably dusty/muddy, flushed and unkempt, Charlie was turned away on more than one occasion by

Eadie’s parents. This action may be somewhat hard to understand as Eadie’s father was a keen

cyclist and the captain of a local cycling club. He would have known the effort that lay behind Charlie’s

journey.

One senses therefore the hand of Eadie’s mother in the rejection of the weary suitor. According to his

son, Charlie’s social skills were lacking and his manner of speech might include the occasional

expl**tive. On the back of one photograph of himself, Charlie has plaintively written, ‘Dear Edie (sic),

I’ve just come to wish you a Very Happy Xmas and for the New Year, every good wish for health and

happiness. Yours always, Charlie.’ Was this card presented on an occasion when Charlie was not

allowed across the portals of the Dee home?

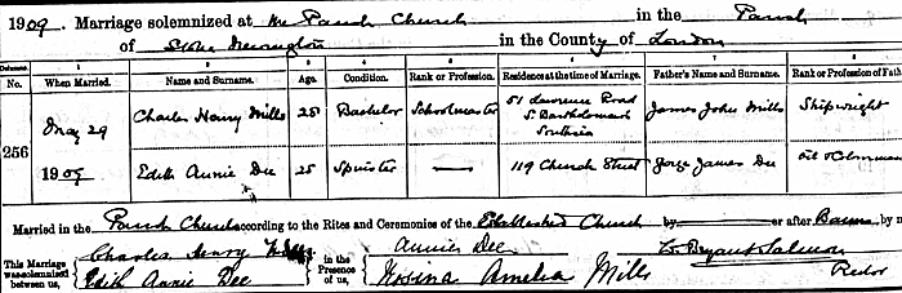

The wedding

Charlie’s love and persistence won through. Four years after leaving college the couple were married

at St Mary’s Parish Church, Stoke Newington (shown below) on Saturday afternoon, 29 May 1909.

The local interest in the marriage of the daughter of a local councillor was reflected in the assigning of

three column inches to the wedding by the Hackney Recorder!

(From l to r): seated at the front, Marjorie Dee and Elsie Dear. Next row, bridesmaids - Violet

Jamieson and Dora Dee; Rose Mills; Annie Dear, Ann Dear, George Dee and William Dear. To

Charlie’s left is Bella Jeffrey. and behind the bride is Archie Mills. Above him is Matilda Mayston.

To the bride’s right are Gertie, Ethel and Eliza Dee with her husband

The ceremony was conducted by the Rector, Rev. E. B.

Salmon. Eadie was dressed in white silk with a pretty

lace veil and orange blossom wreath. She was attended

by six bridesmaids: her three sisters, Dora, Gertrude

and Marjorie Dee, and three cousins, Ethel Maude Dee,

Violet Jamieson and Elsie Dear. The bridesmaids wore

white muslin and silk dresses with rose trimmed,

leghorn hats. Archie Mills was the best man. Charlie’s

presents to the maids were white satin, hand-painted

bags and scent bottles.

The wedding breakfast was served to more than fifty

guests at George Dee’s home, Fairholt Road, Stoke

Newington. Ironically (in view of Charlie’s travels and

travails), the presents included a case of silver salt

cellars from the Clapton Wanderers Cycling Club, of which George had been captain. Charlie and

Eadie left for their honeymoon at Bournemouth – the bride wearing a mole costume with Tuscan hat

trimmed with scarf.

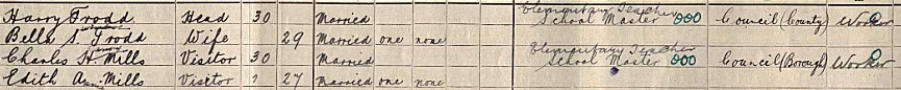

The 1911 census

On census day, Charlie and Eadie were visiting their old friends from college at 162 Avenue Road

Itchen, Southampton.

Their children and early homes

A daughter, Grace Edith, (my mother) was born on 24 June 1912 and Patrick Mills was born on 15

March 1914.

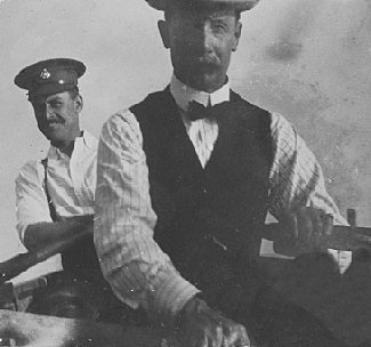

Charlie’s war

After searching for more than a decade, that I have discovered where Charlie served in WWI - and

this was because I identified his cap badge in a photograph. This opened the door for more

information which was found in newspapers. The photo was of Charlie rowing a boat with his father-

in-law, George Dee:

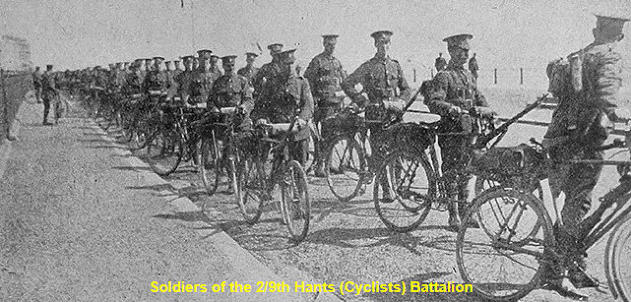

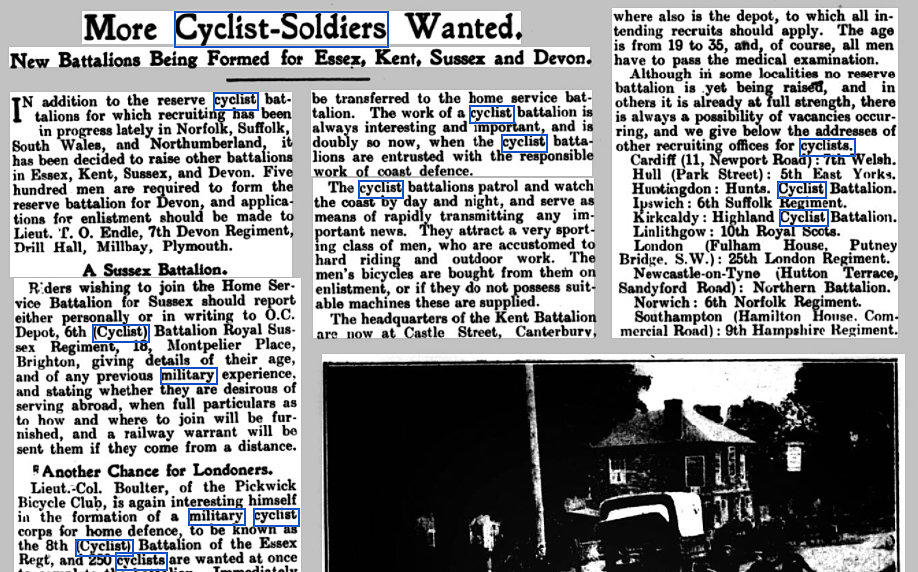

The badge was of the 9th Hants (Cyclists) Battalion. With the invention of the bicycle, horses

suddenly became redundant for many operations of war. Cycles could now be used for

reconnaissance and communications. They were lighter, quieter and logistically easier to support than

horses which needed to be fed, stabled and shoed. It was decided to form the Hampshire Cyclists

Battalion in 1911 and recruiting began in earnest in early 1912. Portsmouth was expected to provide

two divisions. Two sets of uniforms were provided free of charge and while recruits brought their own

cycles, they were paid a cycle allowance of 30s 6d, together with a boot allowance. They were to be

aged between 18 and 35, ‘well educated men who are good cyclists’ and who would ‘do their best to

make themselves good and efficient soldiers’. Later recruitment posters decreed that they should be

a minimum of 5’ 3’’ tall.

Their assignment was to patrol the South Coast from Dorset to East Sussex, including Hampshire. It

was ‘a special line of coast to defend’ and the thinking was that such a Battalion would free the Navy

and the Army to do their duty elsewhere without fear of what was happening at home. The cyclists

were capable of quick mobilisation so as to throw a net around any possible invader. Their training

included rides of more than 100 miles and skirmishes with armed corps.

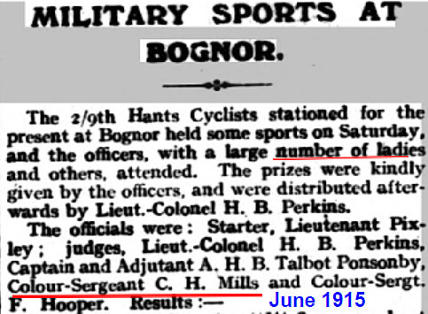

Some cyclists carried machine guns. By 1915, three Battalions, each of 700 to 800 men were

established. Charlie was in the 2/9th Battalion. This was formed at Louth, Lincolnshire in September

1914. It was moved to Chichester and thence Bognor (where Charlie found a home for his family).

Then, in October 1917, the Battalion was moved to Sandown on the Isle of Wight (Charlie was still

attached to the unit as I remember my mother saying he served at Sandown). In April 1918, they were

transferred to Herringfleet, Suffolk and then to billets at Lowestoft in October 1918. Shortly after this,

Charles received another posting.

The 9th Hants Cyclists began as a Territorial Force - this was created as a volunteer component of

the British Army to augment the force without resorting to conscription. They were part-time soldiers

who were liable to serve anywhere on the home front, but could not be compelled to go overseas

(although the 1/9th quickly agreed to serve in India and Russia early in WW1). However, the

Territorials had an identity which was separate to the regular army, to the extent that they didn’t

receive the basic service medals during WW1.

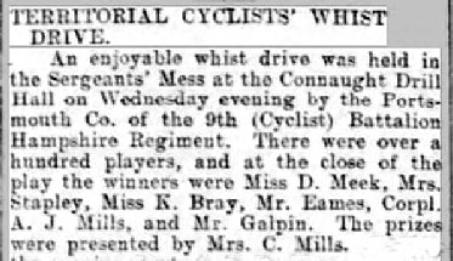

The inference of the news report (shown right) from November 1912 is that Charlie had joined the

Territorial Cyclists by then. The book,

As his wife presented the prizes and his brother, A J Mills (a Corporal) was also present,

surely Charles himself must have been a Cyclist. It was fortuitous that Charlie could make the

transition to the 2/9th in August 1914 because it meant he was on home soil - and close to his

young family - although still being part of the war effort. We are indebted to St Lukes School

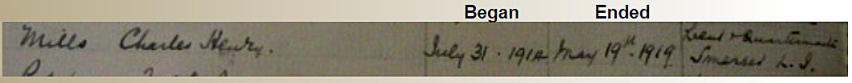

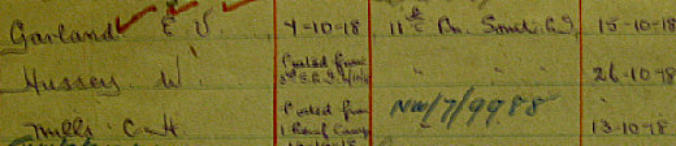

for details of when Charlie began and ended his military career:

Further news items give details of his rank:

The photograph right, shows Charlie in his

Cyclists uniform with what appears to be a

Sergeant-Major’s badge on his arm (inset). It

was taken at Bognor - the Theatre Royal in the

left background is unmistakable. He appears to

be gazing out to sea, single-handedly ready to

repel the Hun!

Now we move to the months at the end of the War. As the St Lukes School entry above indicates,

Charlie had joined the Regular Army - the 11th Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry, which he left shortly

before 19 May 1919, about six months after the War ended. He was a Quartermaster-Lieutenant, a

fairly senior rank.

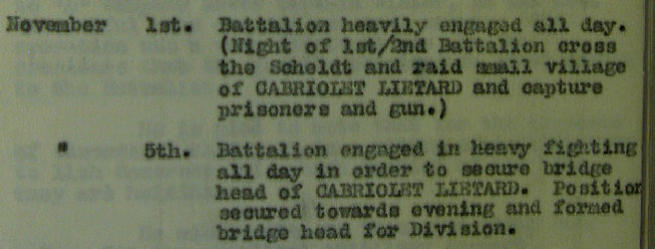

The Battalion was formed in January 1918 and embarked to France in May of that year. Initially they

were employed digging trenches, but later in the year they moved nearer the Front, south of Arras. In

early October, the Battalion moved to the line at Bois Grenier - which was a strongly held enemy

position. An attempt to advance was met with heavy resistance and casualties resulted. A day-to-day

war diary of this regiment exists at Somerset Archives and it relates where Charlie was and what the

regiment was doing.

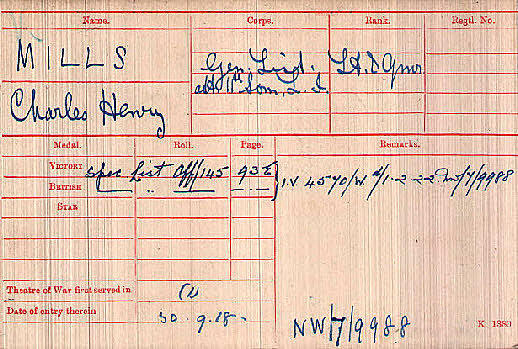

Note Charlie’s Service No: NW/7/9988. His medal card can be seen below.

Charlie had been in a Relief Camp. He disembarked from England on 7 October 1918 and joined the

regiment on 13 October. The War may have been about to end less than a month later, on 11

November, but he was thrown into the thick of things. The Battalion was in reserve at Flerubaix but on

16 October, they were moved up to Bois Grenier, which is about fifty miles south-east of Calais

Six days later the Armistice was declared - and all that was left

was to gradually mop up, return home and be demobbed. On

many of the days Charlie was with the regiment, it was reported

that the ‘enemy artillery was very active’. Men were wounded and

killed and at least one was killed by a sniper. Some change from

cycling around the coast line to being thrust into the din of war!

My uncle said that on one occasion the Quartermaster Stores

was hit by a shell, but fortunately Charlie was absent, reporting to

his commanding officer. On the 29 October, the Battalion was

inspected and those requiring new articles of clothing were re-

fitted at the Quartermaster’s Stores. A little piece of action then

for Charlie!

The War had a sweeping impact on many families and coloured

Charlie’s relationship with his brother Archie. Although they had

been close (Archie had been his best man) Archie was not

conscripted because of varicose veins. While the war was raging

and Charlie was abroad, Archie was appointed headmaster of the

Beneficial School at Portsmouth on 26 August 1907. When

Charlie returned from France, he found his younger brother

working as ‘Head’: a position he was never to fill. Archie was also

a freemason for whom Charlie had ‘no time’

Charlie and Edith’s homes at Portsmouth

Charlie and Eadie’s first marital home was a typical small Portsmouth terraced house at 3 Tredegar

Street, Southsea (below far left). However, in 1912, when Grace was born, the family had moved a

few streets away and was living at the more substantial 26 Rochester Road, Southsea, Portsmouth

(below, second left). This home was about a kilometre from Southsea beach and Charlie bathed there

often throughout the year. Probably, it was a rented property. In 1921, another teacher from St Lukes,

Frederick J Pitchers, was renting the same house. He too had served in the army during The Great

War.

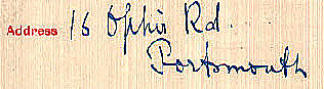

After the war, Charlie and Eadie lodged with Daisy Tuck (a relation of Charlie’s mother) at 5 Playfair

Road, Portsmouth. They then bought ‘Verona’, 16 Ophir Road, North End, Portsmouth (below,

middle) which cost £640. A move to a newly-built home at 74 Chatsworth Avenue, Cosham followed.

Charlie rode to school on a Royal Enfield motor-cycle .

As Cosham became more ‘built-up’ Eadie wanted to move again so another new house, 86 Northern

Parade, Portsmouth (below, far right) was bought for £1,000 in 1937. It was christened, ‘Fairholt’

(which was the name of the road where Eadie had been raised). This was to be their final move.

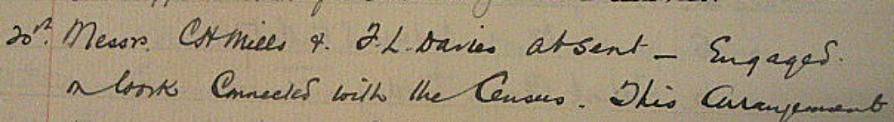

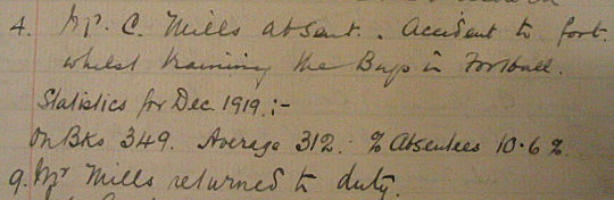

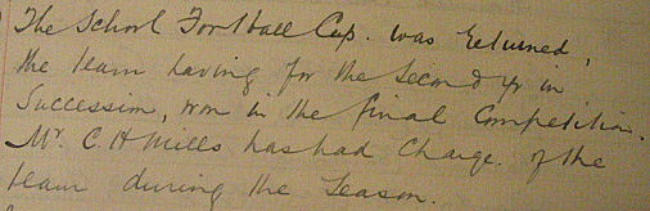

Charlie at St Luke’s School

February 1920

Entries re: Charlie in the school log book:

20 June 1921

The census was taken on the 19 June 1921. Was Charlie an enumerator? When the census is

released, all may be revealed.

It was surprise to me because I don’t recall Charlie kicking a football around with me in the nearby

Alexandra Park.

January 1927

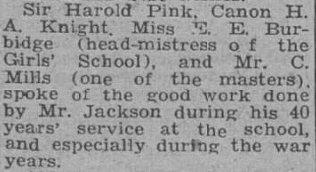

On the retirement of St Lukes

Headmaster in July 1944

When celebrating the School’s swimming

achievements in January 1949

From the two news reports shown above, Charlie retired from teaching between 1944 and 1948. As

he was sixty-five in July 1946, he probably retired around that time.

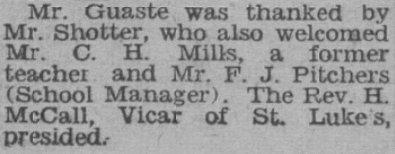

After Charlie retired, on 7 March 1953 (shortly before his death), he participated in a ceremony of

planting grass seed at the new playing field at St Lukes, Hampton Street. Also shown is Mr A C

Maddick (far right) who once took me to Southampton on a train.

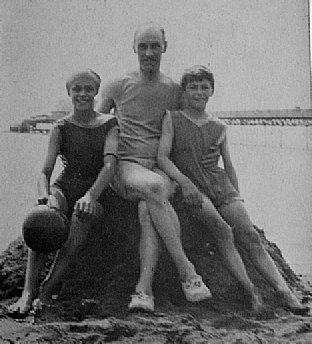

1925 - 1948

Meanwhile, Grace and Patrick were growing older. The postcard above was sent by Eadie to her

mother in around 1925 from Sandown, Isle of Wight which was a popular holiday destination for the

family. That Eadie hopes that her parents do not think the photograph to be too rude gives an

intriguing insight into the family’s moral code. The holiday snaps which have been passed down show

that Charlie and Eadie enjoyed the seaside. Indeed, many of the Dee family spent time together at

various resorts which shows the close relationship between Eadie and her sisters.

The mid-1940s were a stressful time for Charlie. His daughter, Grace,

married a farm labourer in 1945. Charlie and Eadie did not smile on this

match. Then, in probably 1946, Charlie retired from teaching. Earlier that

year, Grace returned to Portsmouth for the birth of her son - and stayed

with Charlie and Eadie for eighteen months. Eadie’s widowed mother,

Annie was also in residence.

Charlie’s beloved Eadie had not enjoyed the best of health. She appears slight in photographs. She

lost weight and her hands were deformed by arthritis. After a prolonged illness, she died (aged 65) at

3.00 pm on 26 October 1948 from a stroke and bronchitis brought on by “fibrosis of the lungs”. If that

bereavement wasn’t sufficient burden, Eadie’s mother who was now living in a nursing home at

Southsea died less than three months later.

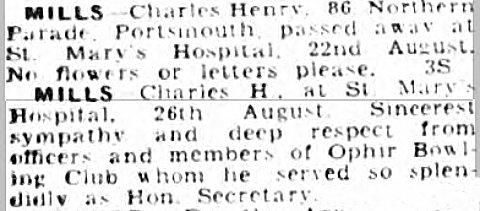

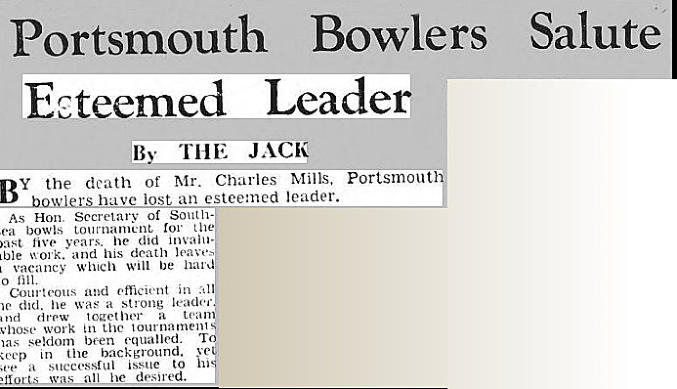

Charlie’s retirement

Charlie’s time now was divided between his bowls

club, gardening and his newly-acquired family. He

had been a bowler for many years and had been

secretary of the Ophir Bowling Club which was

conveniently based across the road from his

home. When Eadie was alive, this was a source of

contention as she demanded that he spend more

time with her rather than his bowls. I remember

him writing in his club ledgers in the front bedroom.

In 1951, he organised the Southsea bowling

tournament. The photgraph tight shows him

watching the Lord Mayor bpwling (See addendum

for more information). He wrote about this

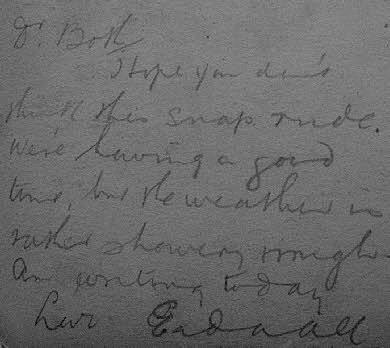

achievement:

Charlie spent a lot of time with Grace and his two

grandchildren. He drove a Morris Minor (GTP 914 -

right) and in the summer we would sally forth to Slindon

Down, the Meon valley and Petersfield. I have sharp

memories of these jaunts, and so clearly enjoyed them.

In the summer, Charlie would hire a beach hut at

Eastney and every day we would all troop down to the

seaside. On one occasion while in hospital he wrote, ‘I

wanted Saturday off to see Grace and the kiddies to

their (beach) hut. You can guess the amount of bits and

pieces that were wanted for the fortnight and I’m hoping

to be out in time to carry it all back home again’.

Mum also took us to a hotel at Ventnor, Isle of Wight, for

a summer holiday. I have no doubt that Charlie funded

this. I also fondly recall him teaching me arithmetic using

a small blackboard and chalk as I was perched on his

knee. The sum of my recollections is that he spent a lot

of happy and instructive time with us.

Charlie enjoyed gardening. He built a rockery at the end

of the garden. There were espaliered plum and apple

trees along a south-facing wall and the garden was

dominated by a beautiful copper beech tree. A heavy

garden roller was parked in the corner. He loved

canterbury bells, sweet williams and fuschias

Although he loved his pipe – and the convoluted operation to set it

alight – Charlie was fit and healthy. As a young man he would swim in

the sea in all seasons. His interest in swimming is also shown by his

attendance of a celebration of the winner of the 1947 cross-Solent

swim who was an old boy of St Luke’s School as a former master of

the school. He thought nothing of cycling to London and back. The

school logbooks notes only two absences for illnesses when he had

flebitis and lymphangitis.

In 1951, he was in hospital for tests: ‘this hall of beds and mixed

smells’. He wrote, ‘the problem is I lose a quantity of blood through the

back passage and until the doctors find out why, there will not be

much progress’. He was diagnosed as having leukemia (like his

mother) and was treated at St Mary’s hospital – where his father had

died. My mother was disturbed because he cried out for a transfusion

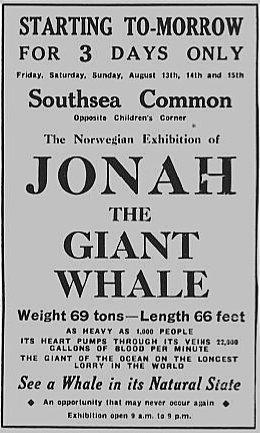

at the height of his discomfort. Near the end on around 14 August

1954, he was allowed out of hospital and typically took his family on a

trip. We were introduced to Jonah, a huge (and stinking) whale

carcass 66 feet long and weighing 69 tons which was displayed on a

trailor at Southsea Common. Charlie died about a week later on 22 August 1954. I distinctly remember

Mum sitting on the side of my bed to tell me the sad news. The effects of his estate amounted to

£3797 5s 2d.

Epilogue

Eadie was ‘vivacious, a loving, faithful wife and a good cook’. She clearly had middle-class standards.

Charlie appears stern and brusque – a man who didn’t leave his school master’s manner behind at

the school gates. His son was a little in awe of him and I clearly recall Charlie threatening to ‘come

down on me like a ton of bricks’ on several occasions. Few of the photographs show him smiling.

However, I have been taken to task about this description by a cousin who has pleasant memories of

a bright and breezy character.

He was impatient. To have a deaf wife and daughter must have put a

strain on the family. His daughter remembered that he drew attention

to her left-handedness and unladylike feet. Archie was more outgoing

and made friends easily unlike Charlie who was inclined to speak his

mind and had few friends apart from his bowling cronies.

The family was comfortably-off and lived in homes of good quality.

Even in 1932, Charlie was driving a Singer car (right).

Charlie inherited a natural talent for working with his hands from his father,. He made well crafted

items of furniture such as a mahogany bureau in the living room. He was a competent artist (see the

example below) and had a flowing style of handwriting.

My last memory of grandpa is of him waving goodbye to us all from an upper window of St Mary’s

Hospital, Milton, Portsmouth

Postscript - a glimpse of the artistic talents of Charlie and Eadie

In 1910, Eadie’s sister, Dora Dee invited contributions to her autograph book. Below are the creations

of Charlie and Eadie

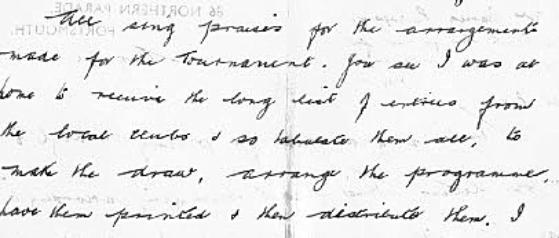

Charlie and Ophir Road Bowling Club, Northern Parade, Portsmouth

Examining news reports, Charlie was Secretary of the Ophir Bowling Club from 1947 - he worked

from a desk by his bedroom window from which he could see the bowling greens. However, as Eadie

died in 1948, I rather think that start date should be 1948.

In addition to these duties, he was also Secretary of the Southsea Open Bowls Tournament. This was

a prestigious event being opened by the Lord Mayor and reported each year by the local

newspapers. Among the contestants were Alex (a winner one year) and Jimmy Scholar (Portsmouth

FC and Scotland international footballer and later Cardiff City manager), together with Harry Ferrier

and Duggie Reid who were also Pompey footballers.

Hundreds of bowlers from all over Britain competed at the Southsea tournament, so many that as

well as the rinks at Southsea Common, those at Canoe Lake, Milton Park, Pembroke Gardens and

Southsea Castle had to be pressed into service. Charlie would have been responsible for the setting

up and smooth running of the event and was often publicly thanked for his efforts.

When his illness took its toll, he continued to work and in July 1954 his absence through illness was

commented on as was his work which was performed despite his indisposition. The following month,

these notices were carried by the Portsmouth Evening News

At the annual meeting of Ophir Bowling Club in November 1954 a ‘silent tribute’ was paid to Charlie.

A further reminder in the form of the Chas Mills memorial Trophy was set up. The Portsmouth

Evening News also ran this brief eulogy:

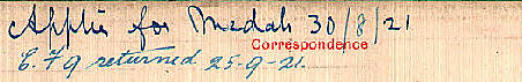

Charlie’s WW1 Medal Card

Note that Charlie applied for his medals about two years after

he was demobbed -and sent one back about a month later.

The two medals were the Victory Medal (awarded to all who

received the 1914 Star Medal or the 1914-15 Star Medal and

who served between 5 August 1914 and 11 November 1918)

and the British War Medal (awarded to all who served between

the two dates mentioned earlier). He didn’t qualify for the

1914-1915 Star medal because he was part of the Territorial

Force then, not in the Regular Army. Evidently, he returned the

Victory Medal because he didn’t qualify for this as he didn’t

receive a Star Medal.

Charlie was back in uniform during WW2. The 1939 Register

reveals that he was an Air Raid Warden and the photo below

shows him as a Corporal in the Home Guard - complete with a

single medal ribbon. Worn with pride, I feel.

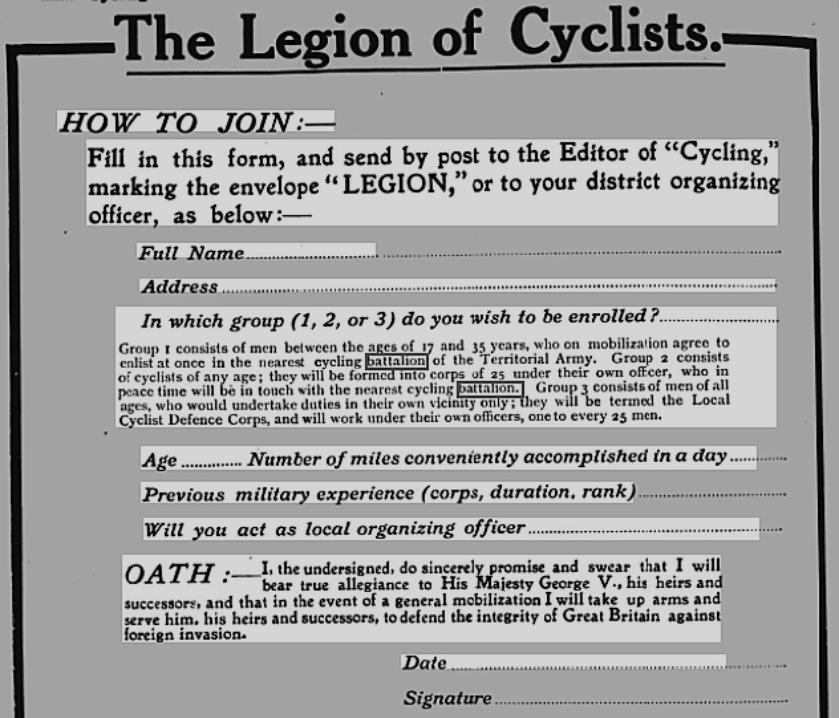

The form Charlie (31) and Archie would have signed to join the Cyclist Battalion in 1912

“Portsmouth in the Great War” notes that

the Drill Hall was the base of the Cyclists.

Edith had given birth to her daughter only

five months earlier.

Archie’s varicose veins meant that he

wasn’t accepted in the Battalion when

war broke out.

‘Military Cyclists’/‘Territorial Cyclists’